Article by Lizzie Crudgington, Bright Green Learning

When helping clients design online meetings and workshops, we often face all sorts of assumptions about what you can and cannot do online. Usually we find that you can do MUCH more than you first assume. What you need is some creativity and thoughtful planning!

Here I share a few examples of some of the more unusual ways in which I’ve used Zoom in the last months for more informal online convenings and gatherings, such as various birthdays and other fun events. These are being shared in the hope that these times push us to challenge our assumptions about what we can and can’t do online, have fun testing new ideas (for example with kids, friends and family- push yourself to try new things in a ‘safe space’), and then find ways to adapt and integrate more lively and creative interactive elements in our professional as well as personal virtual lives going forward.

I’ve included some ‘how to’ steps below with these 20 examples, revealing some of the things to think about when preparing for these online activities. If you feel so inspired – have a go! And reach out with questions if you’d like more details. Included below:

- The Maker Challenge

- Read Together Online

- Sewing Workshops with Grandma

- Playing App-based Games

- Online Face-painting Game

- Hum that Tune

- Charades

- Mind-meld

- Pictionary Online

- Online Quiz with Riddles and Emoji Questions

- How Well Do You Know…? Game

- Guess the Song

- Musical Statues

- Blow Out The Candles on the Cake

- Choose a Themed Virtual Background

- Get Physical with a Speed Hunt

- Collective Cocktail Making

- Online Spinning Wheel

- Celebrity/Who’s in the Bag?

- Taking Cranium (the Board Game) Online

OK, let’s start!

- The Maker Challenge. The week before Easter, we planned an online family party and asked everyone to get scrap paper ready. We ran the party on Zoom with families in five locations. Each family had 5 minutes to make their Easter Bonnets from scrap paper – ensuring the camera was lined up so we could see one another’s creative process – and of course we wore the bonnets for the remainder of the party.

(Other versions: Instead of an Easter bonnet, make a space helmet, pair of glasses, diving mask, a dress, a bouquet of flowers, a trophy, a car, the strongest bridge, the tallest tower…. The fun is in the making! And why stick to scrap paper? Could be modeling clay, twigs found outdoors, LEGO…)

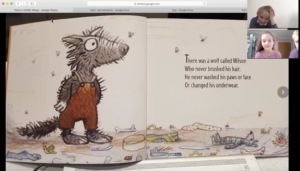

- Read Together Online. Take photos of the pages of illustrated children’s books and upload these to Google Drive. In Zoom, screen-share the book and simply click through the pages. We’ve had reading sessions with grandparents, as well as 6 and 7-year-old cousins reading their favourite books together.

- Sewing Workshops with Grandma. This was really simple. We just set up Facetime (could use Zoom or other platforms too) with the cameras carefully positioned, and away we went. Home-sewn face masks – tick.

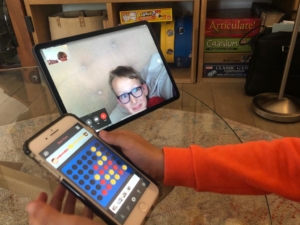

- Play App-based Games such as Connect 4 and Rummikub – whilst using Zoom or Facetime to interact. We use two devices (a smartphone and tablet or computer) so that we can chat and see and hear one another’s reactions during the game playing – maintaining the social dimension.

- Online face-painting game. How about it? Also during the Easter party, we played a face-painting game using only an eye-liner pencil. We gave a willing volunteer the challenge of giving face-painting ‘instructions’ to everyone else (based on an image provided), without using certain words (i.e. they couldn’t use the words rabbit, bunny, nose or whiskers). We did the drawing part with backs to the cameras and then, once complete, we had ‘the big reveal’. Ours was a Easter-themed bunny, but you could choose any face-painting theme. An interesting exercise in the power of communication too – usually with entertaining results.

- Hum that tune. To play this one, we combine Zoom with WhatsApp. The name of the tune is picked from a hat, by the “game master”, photographed and WhatsApp’d to the player who’s turn it is to hum. Then those ‘guessing’ the name of the tune race to submit the correct answer – either to a WhatsApp group or the Zoom Chat. (We find that using the Chat for answers works better than shouting out the answer as it can be hard to hear the person humming, especially if the group playing is large.)

- Charades. As we did for for ‘Hum that tune’, we combined Zoom with WhatsApp. The charade is picked from a hat by the game master, photographed and WhatsApp’d to the player who’s turn it is to act out the charade. Those in the same team call out over Zoom.

- Mind-meld. The idea of this team game is that a word (suggested by the one team) is given to all players on the other team who then have 30 seconds to each write down three words associated with that word. If there is one word in common in what all players in the team write down, they win a point. To play this, the word is called out, and players simply use simply pen and paper to write down their three associated words. After the 30 seconds they then hold their papers up to the webcam so everyone can see what they wrote and whether or not they win the point.

- Pictionary online. For this, we’ve done it in various ways. One option is to use the whiteboard in Zoom and have players ‘annotate’ it using the ‘scribble’ tool. Others can then guess either shouting aloud or submitting their guesses via the Zoom Chat or a WhatsApp group. Another option – which allows for a better touchpad drawing experience – is to invite players to use a drawing app on their smartphone or tablet. If they connect it to their computer via USB, they can then screenshare what they are drawing. The downside of this option is that it requires a bit more tech set up (getting people to install drawing apps on their devices), and you need to change who is screen-sharing every time there is a change in who’s turn it is to draw.

(Another option: use paper and pen in view of the webcam.)

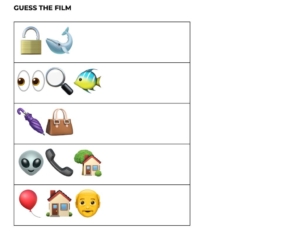

- Online Quiz. There are so many ways to do this. A few things we’ve done to ensure the quizzes are fun and interesting to all – ask everyone to contribute questions in advance. Include riddles and try some questions with emojis (e.g. Which film is this?).

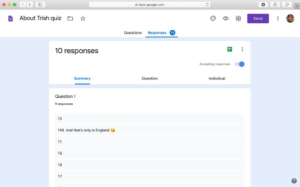

- How Well Do You Know…? Game. A great variant on the quiz – especially if you are throwing a party for a birthday girl orboy – here Person X. We asked everyone to submit questions about person X in advance (e.g. Where were they born?), and we created a Google Form with questions numbered 1 to however many questions you have. Note: Don’t actually include the questions themselves in the form – just the question numbers. During the party, announce the game and send everyone the link to respond to the Google Form. Read question 1 aloud and invite each player to write their response in the form. Repeat for question 2, and so forth. (The fact that the questions aren’t written into the form keeps an element of surprise!). Make sure that person X also responds in the Form! Once you’ve gone through all the questions, go the summary of responses (in the Google Form) and screen share these, looking at them question by question. Person X reveals the correct answer (and all are amused by the variety of responses). If you like, you can give points for correct answers but this is totally optional.

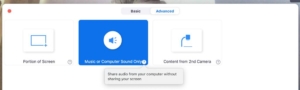

- Guess the song. Different to ‘hum that tune’, in this game we play songs from a playlist in Spotify and it’s a race for players to guess the song – using the Zoom Chat or a WhatsApp group. To ensure a good sound quality, mute everyone and play the music through your computer, clicking on ‘Share Screen’ / ‘Advanced’ / ‘Music or Computer Sound only’. Not only does this help with sound quality – it also means people can’t see the songs you are selecting to play, which would defeat the object of the game.

(Another version of this game: What’s the next lyric?)

- Musical statues. A classic party game, super for expending some energy and loosening up bodies. As in ‘Guess the Song’, play music for musical statues using ‘Screen Share’ / ‘Advanced’ / ‘Music or Computer Sound only’. Before starting, check everyone has their web cam set up such that you can see them in their ‘dancing space’. And then play musical statues as normal – when the music starts every begins to dance. When the music is stopped, everyone freezes (stops dancing), and the person who is still moving is out of the game. This continues until there is one person left. A great and easy party game for small and big kids.

- Blow out the Candles on the Cake. Just for a bit of fun – when it’s a birthday, have a real (or ‘model’) cake with a real candle held up close to the web cam and have the birthday boy or girl blow the candle out from their computer (close up to the web cam). Tip: Make it tough for them, and get them really huffing and puffing (with little effect on the flame) before you blow it out once and for all 🙂

- Choose a Themed Virtual background – such as bunting or a photo of your favourite bar! In Zoom, go to ‘Choose virtual background’ (next to the video options in the bottom control bar) and you can upload an image of your choice and select it as your virtual background. (Note: This works best when your own background is neutral)

- Get Physical with a Speed Hunt. This is another great way of bringing some movement and energy to online events. Prepare a list of commonplace items and mini challenges and have different household / office teams race to complete them. g. ‘Find something stripey’, ‘Find something that makes music’, or ‘Take a selfie of all your team in a wardrobe’. Either have everyone return to the web cam as they tick of each thing on the treasure hunt list, OR have them take a photograph at each step and WhatsApp it to you.

(Another version of the game: Create mixed teams (across multiple households / offices) and use the Breakout rooms function – putting one mixed team per breakout room to complete the speed hunt. Note – for this option you can’t ask everyone to take a selfie of themselves together in a wardrobe!)

- Collective Cocktail Making in Various Kitchens. Need a drink? Rather than just take a break, make the drink preparation an online activity. It requires a little prep, deciding on your cocktail and sending out an ingredients list in advance with enough time for everyone to source things (e.g. mint, red berries, soda water, lime, cucumber…) To run it’s really easy. Just invite everyone to move their devices to somewhere safe in the kitchen and line up webcams so everyone can see one another well, and then walk through the cocktail making steps, and once made – enjoy! A refreshing and energizing break.

- Screen-share an Online Spinning Wheel – such as the ‘wheel of names’. I love this and use it for all sorts of activities. For example, if playing a team-game online, use it to randomize the teams. Put all names in the wheel, screen-share it and and spin it to see who goes with who (e.g. the 1st 4 are together, 2nd 4 are together, etc.) Use it to choose which games you’re going to play next (e.g. will it be Pictionary, charades or treasure hunt?) Use it to see who gets to go next (from all the names). So many applications. Get creative! And keep people on their toes with the element of surprise. (Note: the default setting in ‘wheel of names’ is that, once selected by the spinner, the name disappears, but you can change the settings if you want to keep all items in the list. You can also change the colours, sounds, spin time, etc. It’s very versatile.)

- Celebrity / Who’s in the Bag? For this one, you need to know how to play the game IRL (in real life), then this online version description will make sense. You also need a dedicated games master. It’s a lot of fun, but the games master doesn’t get to play. The game works as normal, only the games master has the list of celebrity names and, as people can’t pick the cards or papers from a bag. The games master uses lightning speed fingers to type the names into WhatsApp and send them to the player who’s turn it is to make his/her team mates guess the names. Every time their team guesses an answer, you send the next name. As it can go really fast, I try and queue up the names so that I just have to press send. You can also cut and paste them from a list (make sure you have three copies of the list at the start: one for each round – with the names in a different, random order in each list). For scoring – count up how many names each player gets in 45 seconds (ask someone else to manage a timer!!) by looking at the number of names sent to them in the WhatsApp thread. At the end of each turn, write ‘END TURN’ into the WhatsApp thread so you can keep track of how many names they got in each round.

- Take Cranium (the board game) Online – renamed ‘Corona-ium’ 🙂 For those who are becoming masters managing Zoom calls, you can put a number of the ideas above together and take the board game Cranium online. Cranium combines games like Pictionary, charades, hum-that-tune and quiz questions, so see notes above on running those. Take a photo of the Cranium Board and put this into a Google slide (or make one up of your own design). Make and name a coloured shape per team as the pieces to move around the board (using ‘Insert’ / ‘Shape’). Then designate someone to be the scorer (ideally not you). Doing it in google slides in this way you can share the link with everyone (view only) so that at all times people can see the state of play. From time to time you can screenshare it too. If you have the board game, you can take photos of loads of the cards and have these in your photo library ready to send out to people via WhatsApp or pop them into a google slide deck that you screenshare. If you don’t have the board game (and I prefer this option with an international group), rather than picking cards, before playing ask everyone to send you (privately) 5 quiz questions, 5 famous people, 5 things, 5 songs, etc. Compile these and use them for the game, drawing on them randomly. Caveat: A player can’t give an answer they submitted so you need teams of at least three.Top Tip: As this game has lots of moving parts, I like to give different people the ‘lead’ on different topic types. e.g. One person reads out the quiz questions. Another does the Pictionary. Another the Charades, etc. This means you can participate and enjoy the game too, rather than just being the games master permanently.

We hope that these 20 examples give you some ideas for how you might adapt the above for your next online gathering, whether it is in a team meeting, a learning activity, or another fun gathering with others online!