(Photo by Martino Pietropoli on Unsplash)

“What is a DACUM?” I asked, when I received an email inviting me to join one from an IAF learning webinar co-presenter.

DACUM, which stands for “Developing a Curriculum,” is an occupational analysis technique developed in the 1960s that employs a panel of master practitioners in a field to “capture the observations of high performing, incumbent workers regarding the major duties and tasks included in an occupation”. This descriptor was included as a part of the brief from the host of our DACUM, the Eastern Kentucky University (EKU) Facilitation Center (Facilitation.eku.edu).

A DACUM analysis can form the foundation for the development or updating of competency-based curricula. The occupational profile and curriculum developed can then be used to inform the design of university, vocational or training courses and programmes. Whatever your occupation – engineer, designer, project manager, trainer – there could very well be a DACUM behind it all that informed your learning journey.

It was a new experience for me, and I thought it might be of interest to others how this behind-the-scenes process works.

How a DACUM works

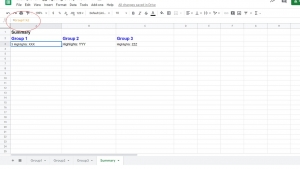

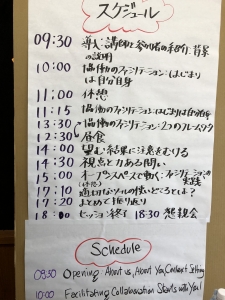

The DACUM is a highly structured, multi-step facilitated process. It starts with the work of a panel of experts, on which I participated, and this step produces a first draft occupational framework. The framework goes through a number of other steps, including a shorter validation workshop with another group of facilitators, a management review, task analysis, and then this outcome is used to support curriculum development or to update an existing curriculum.

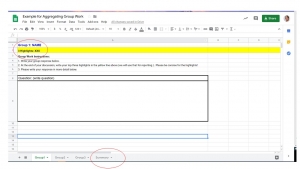

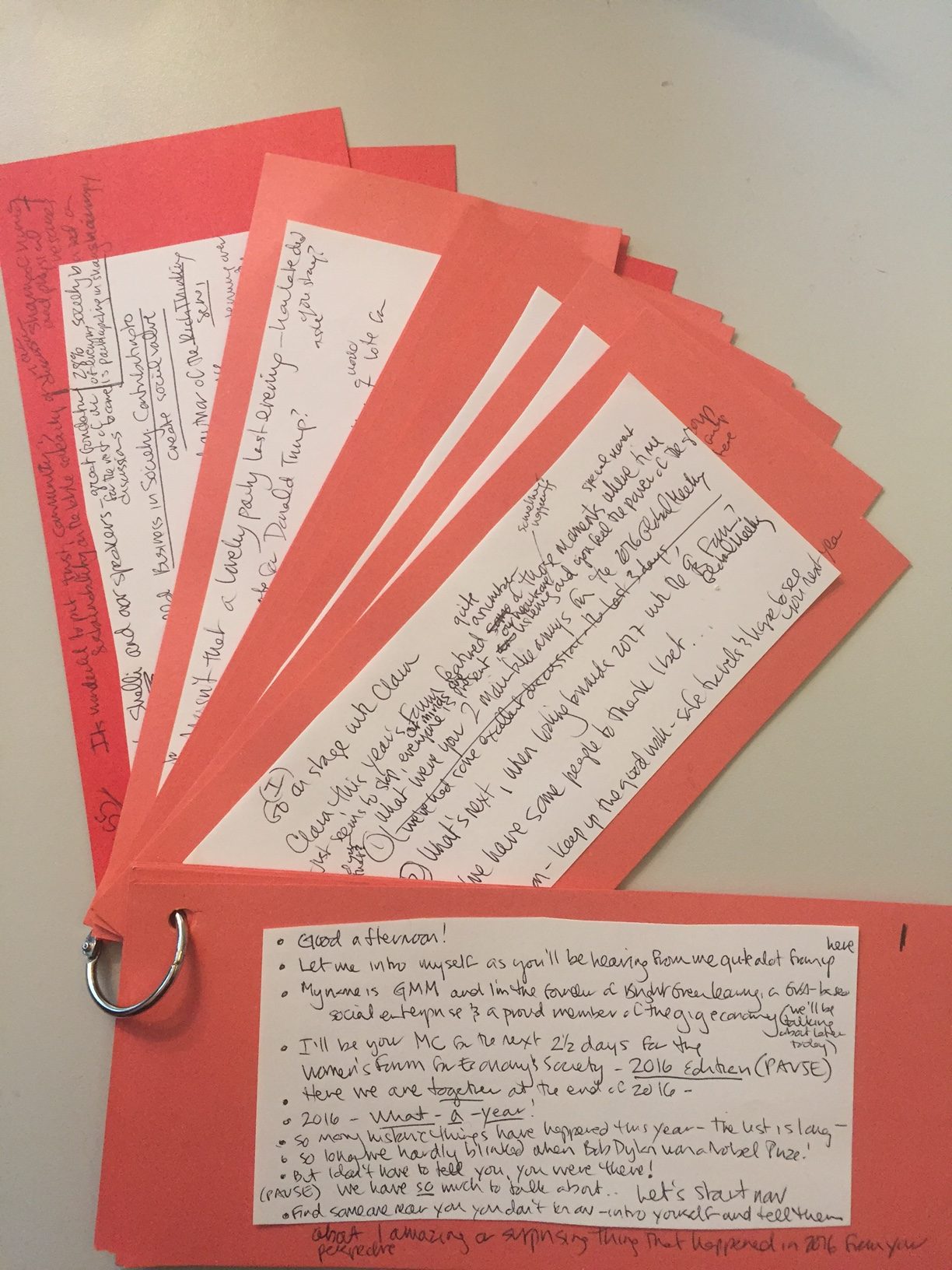

Our DACUM process was virtual and held over two full 8-hour days using Zoom and an online whiteboard. In advance the EKU team kindly sent us each a parcel that included a printout of the slides, a set of worksheets, as well as some fidget toys, a doodle pad and colored pencils, and a bag of lollipops and sweets. The expert panel was composed of 8 senior facilitators located in Canada, the USA, Switzerland, and Jamaica. Collectively we had 199 years of experience as facilitators! An initial occupational background exercise helped us understand the range and diversity of the panel members’ experience and perspectives, which is useful in analyzing and understanding the outcomes from the group. This included identifying the industry or sector with which we each work, as well as the languages we use, and the different specializations we had.

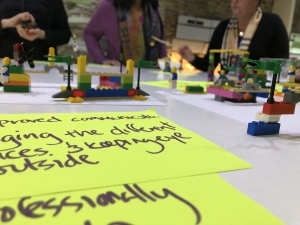

After introductions, we started Day 1 by collectively developing a working occupational definition for a Facilitator, comprising short statements on what they do, how they do it, and why. This exercise sparked an intriguing discussion that exposed some differences in how we approach the role of the facilitator, feeling more or less comfortable using words such as leader, manager, guide, and not always agreeing in these early conversations. Because Day 1 of a DACUM process is a generative/brainstorming day, if any one facilitator had something in their practice or vocabulary, it is captured. On Day 2, however, we worked together to go back to what we generated on Day 1 to dig a little deeper into the meaning, and to refine, reduce, and agree on the core elements. In all of our discussions, the shared norms on which we agreed included having balanced conversations and not use “killer phrases,” which may work to take ideas or suggestions off the table (“I don’t do it that way!”). Instead, we aimed to listen and dig into the essence of what was being shared. We often helped each other find words to describe concepts.

Facilitating the DACUM

The process was skillfully facilitated and managed by EKU (bravo!) A Miro board was created to support “display thinking” and to capture the outputs of the discussions. We were all surprised that the facilitator of the process took on the rapporteuring role, writing everything on the Miro board for us while we discussed ( the panelists noted that when we facilitate we normally ask participants to do the capture work). For the first 1.5 days of the DACUM we did everything together collectively in plenary (interspersed with individual thinking work). This was the case until the very end when time constraints made it more efficient to do some of the final analysis in pairs.

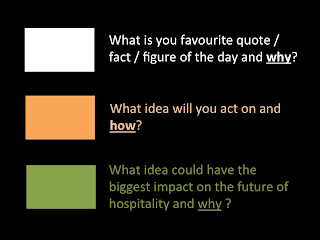

The DACUM workflow process is rigorous and methodical. All tasks and terms are clearly defined to reduce differences in interpretation, and conventions established for labelling (e.g. three words – verb, qualifier, noun) to ensure that responses are similarly captured and easily compared. After developing the working occupational definition, we went through a series of steps to identify and winnow down the major duties of the facilitator, and then within each duty a set of differentiated tasks. As we reviewed each duty and task set, we identified the associated knowledge, skills and traits. At the end of the process, we undertook a series of ranking exercises to share our perspectives on how critical the duties and the tasks were in relation to one another. We also indicated, from our perspectives, which of the duties/tasks would be most useful for new facilitators to learn, and which we felt there were gaps in the current facilitation training on offer.

Identifying the occupational profile of a facilitator

The DACUM was not simply a platform for a set of senior Facilitators to present what we do, to differentiate ourselves from one another, or to judge the merits of the different approaches. We acknowledged the differences in our clients, our tools, and even our language. The overall goal of the DACUM was instead to identify what was at the core of our shared practice. The invitation to diverge on Day 1 in order to generate the most exhaustive possible list of Duties and Tasks that could be identified from across all of our practices, was then in Day 2 reviewed, clustered, discussed, and refined to identify the core Duties and Tasks on which we could all agree.

It was energizing to be led through a structured process to share my practice as a facilitator using the DACUM format. It was also an outstanding peer-learning opportunity for me to spend 16 hours with 7 other highly-experienced facilitators deconstructing their well-formulated practices, which in some cases differed from my own and gave me some good ideas. For example, I was impressed with the steps that some of the facilitators took in the post-workshop/follow-up stage of their work – including how they ran their debriefing sessions, their reporting processes, and how they were using AI tools in different ways at this stage.

In trying to be comprehensive in our identification of the Duties of a facilitator, we identified “Administration” as one of the set, which then was reframed as “Manage Facilitation Resources”. Initially I couldn’t think of many related tasks, but in analyzing that duty we collectively defined a long list of resource-related tasks that facilitators undertake (manage a supplies inventory, manage technology resources, keeping certifications current, setting up folder structures, adhering to GDPR compliance with documentation, etc.). Many of these tasks are mechanical and we may undertake them without much thinking, and they are virtually invisible to others. However, they take time, can be done with varying degrees of effectiveness, and most importantly are not typically included in training for facilitators.

Our DACUM panel’s work now goes out of our hands and into those of other facilitators in subsequent steps. I am eager to see how our initial thinking is further validated and shaped, and how it ultimately informs facilitation curriculum development. As both a trainer and student of facilitation, the experience was valuable and both what I learned from my peers, as well as our output will undoubtedly inform my own work.