On 9 April 2008, 85 IUCN Staff and visitors welcomed David Allen, author of Getting Things Done (GTD), to IUCN – International Union for Conservation of Nature – at its HQ in Gland, Switzerland. Through a contact of a staff member, David offered to run a full day pro-bono GTD training day event in the Main meeting room of the building. We invited other local GTD enthusiasts to join us and had a full house that day. I was a honored to host in my role as Head of Learning and Leadership at IUCN at the time.

Around that time, my Unit had been working with teams in IUCN to introduce the 43 folders system from Merlin Mann, inspired by David’s approach, as well as developing email etiquette and guidelines for staff. Even back in 2007, email was already taking over people’s work lives and producing friction in work flows. That day in IUCN was my second meeting with David and his team, as I had joined a GTD workshop in London (Walking Around with Nothing in Your Head: Getting Things Done) in October 2007 to experience what our IUCN day would be like – I found it thought-provoking, powerful, practial and highly entertaining!

Two further occasions to connect with David and the GTD team arose after his visit. I was delighted to be a speaker on two panel sessions at the first GTD Summit in San Francisco, CA in March 2009. Already well known in the tech industry and private sector, the system was expanding into non-profit and education applications. My panels were “Good Things Getting Done: GTD Serving Service” and “GTD and Education”, where we shared experiences from these different contexts. Included were nerdy details on how my team was introducing it into IUCN, and other use cases from academics, teachers and practitioners in training and learning.

I shared this application story further as a guest on an early podcast with David #19 GTD and Global Sustainability (March 2010) exploring how people working in sustainability jobs could use the approach. Listening to that podcast again last week was like opening a time capsule! Recorded 16 years ago, I listened to my younger self with some apprehension. However, overall I think the discussion holds up as I shared tips about how to socialize new processes into old organizations, reflected on the impact of the 2008 financial crisis on the non-profit sector (as we endure another wave of contraction here in 2025/6), and was reminded of the origin story of my social enterprise Bright Green Learning which I had just launched at that time.

It was 25 years ago, this month, that David launched his first book and the GTD system. That number both surprised me and inspired me to reflect on how I am still using the GTD approach, almost 20 years later, and how I have integrated it into my own unique productivity dashboard. It is amazing to me how much of the system I am still using.

Things that stuck

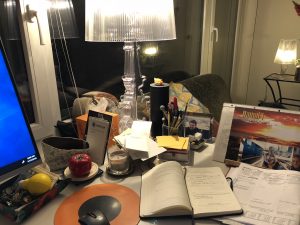

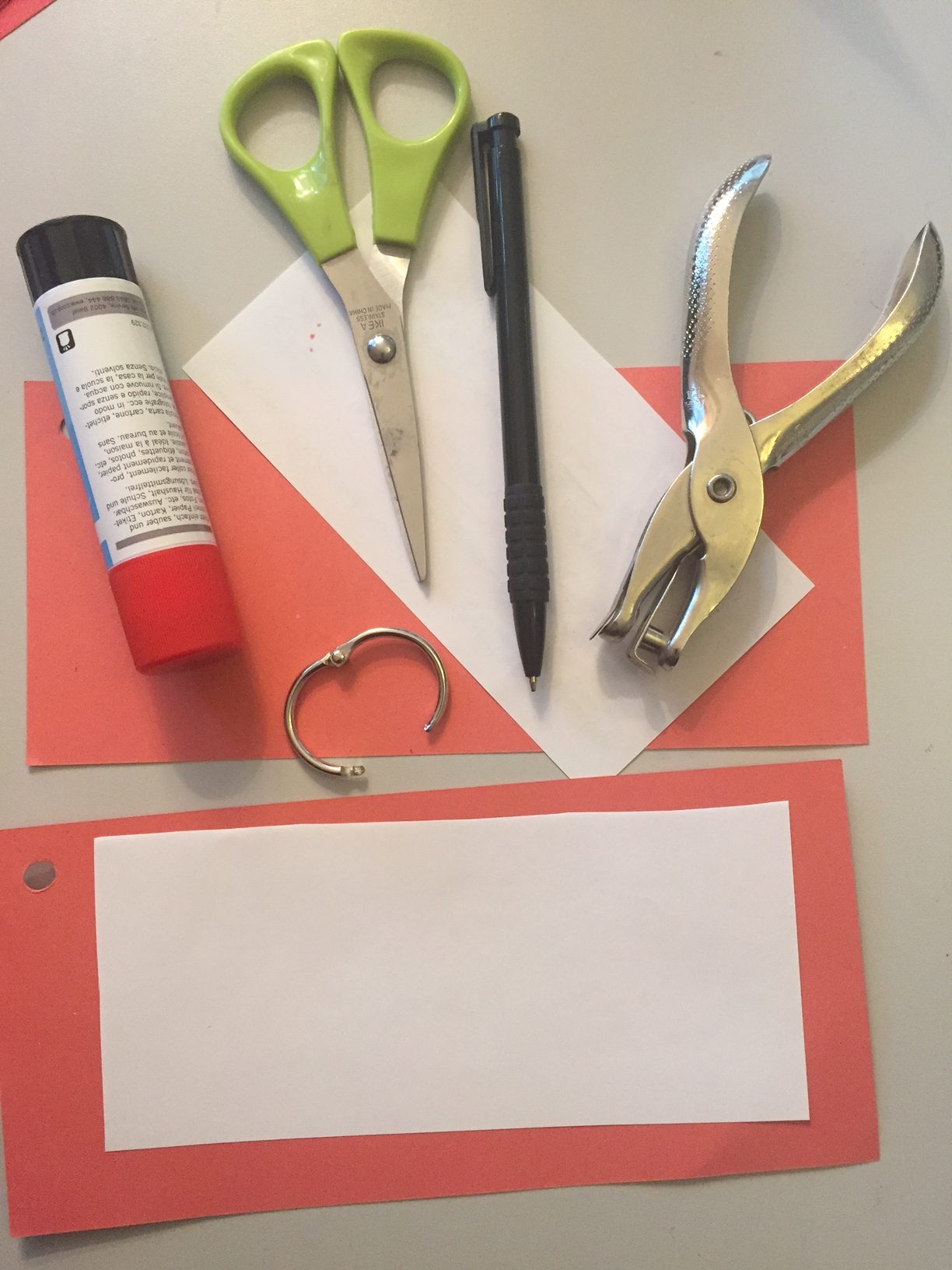

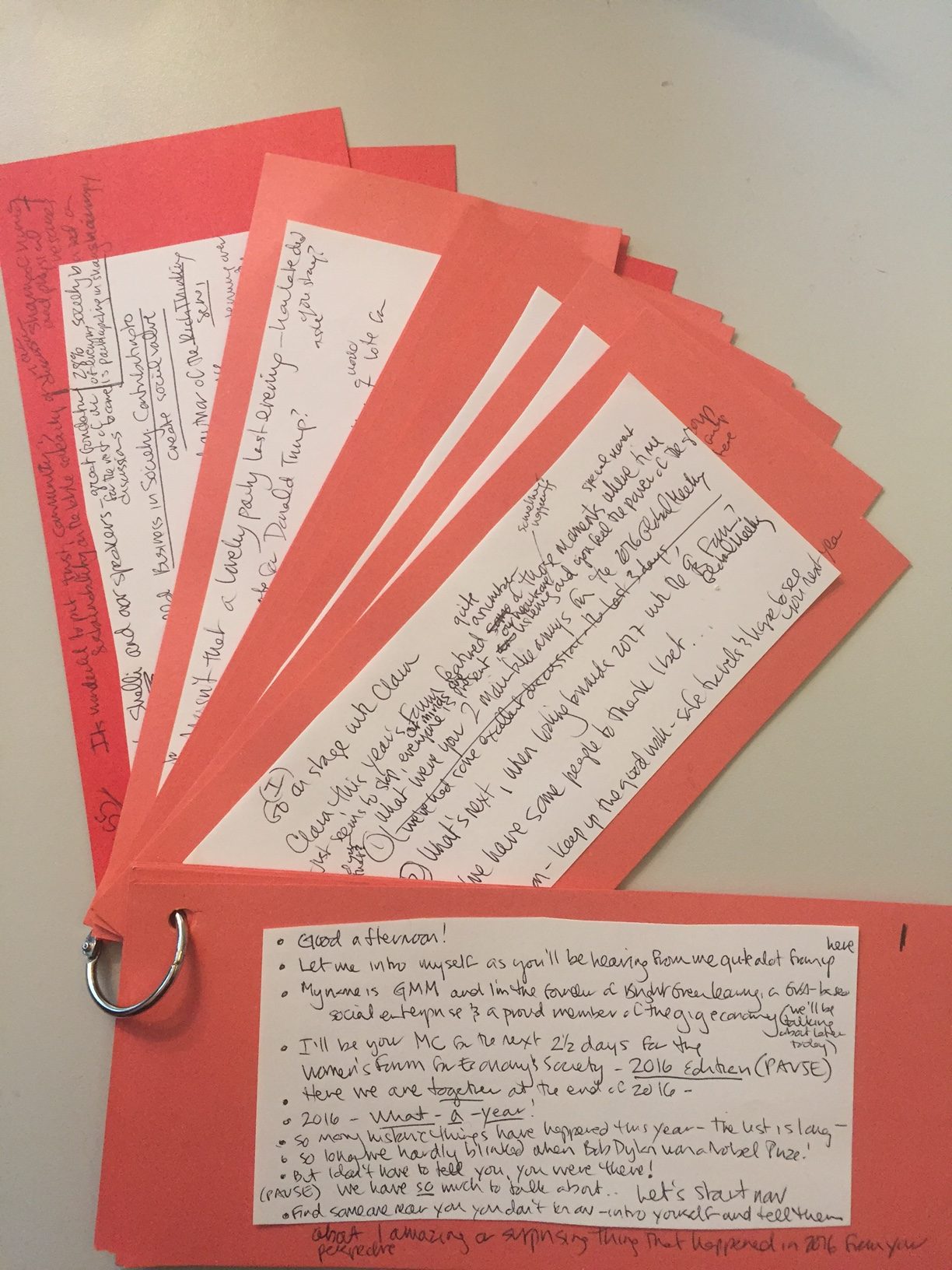

Lots of folders: I still use paper folders because I purposefully keep quite a lot of my work flow process analogue. I think it helps me slow things down to a more reflective pace and the physical reminders of what is active is helpful for how my brain works. I use my tickler file (days, months, contexts), and I keep my projects organized in dedicated folders that are alphabetized in a stand up file. I regularly use my label maker.

Context lists: I have my context lists (@Work email, @work computer, @home email, @home computer, @Waiting for etc.) organized in an A5 Atoma DIY hand punched notebook. However, the granularity and thus number of contexts proliferated over time, and many of these lists got too long after years of keeping them (and not doing those things). My @someday/maybe lists were pages long, so I retired a few contexts and found some other ways to capture ideas versus tasks.

Weekly Review: I also still do a weekly review at the end of each week, although I have a more narrative approach now and use prompts from my Intelligent Change Productivity Planner to guide me. I picked up some handy annual review questions from GTD that I folded into my end of year reflection and planning (Starting the New Year Gently: Structuring Your Personal Reflection and Planning). David asks great questions!

Things that didn’t

A number of GTD elements have come and gone over the years, some regretfully. I haven’t been using the 2-minute rule (if you can do it in 2-minutes just do it and don’t put it on your list), but need to bring that practice back. I never mapped over my digital space fully into GTD (email and Dropbox folders) but set up my own system for archiving and finding things. I have gone in and out of zero-inbox, but still find it terribly hard to keep up with the digital flow when you are juggling multiple projects and have your personal and professional inboxes synced. I also have boxes and boxes of those physical folders from past projects that I now need to digitize – 16 years later those paper project folders number over 400! I need to start scanning these artefacts, and get into the practice of doing so right away once a project is finished (one of my 2026 goals).

GTD remains a treasured part of my productivity dashboard, embedded and intertwined with other practices and tools from CaveDay, Relay FM’s Deep Focus podcast, Cal Newport’s Deep Work, MacSparky’s Productivity Field Guide, Intelligent Change’s Productivity Planner, my NeuYear Focused Wall Calendar, and Lett’s Quarto agenda (btw, no sponsorship, just fangirl!) These tools are complemented with other tips and tricks that I have picked up over the years. But GTD was my first system and I see upon reflection that much has had longevity in my practice. I am proud to have contributed a little to its journey, from the non-profit and sustainability application perspective. Happy 25th Anniversary GTD!