Like tectonic plates, our understanding of different concepts in our world of work slowly, collectively shifts. Like in the natural world, parts may move at different speeds, and change may be initially imperceptible from some perspectives, but things are moving nonetheless. Changes in terminology often accompany these shifts; yet may be offhandedly dismissed as jargon by those who have not been involved in, or perhaps agree with, the new shift in thinking.

Like tectonic plates, our understanding of different concepts in our world of work slowly, collectively shifts. Like in the natural world, parts may move at different speeds, and change may be initially imperceptible from some perspectives, but things are moving nonetheless. Changes in terminology often accompany these shifts; yet may be offhandedly dismissed as jargon by those who have not been involved in, or perhaps agree with, the new shift in thinking.

Behind jargon however is something; some conceptual change, and it is interesting to sift out the nuance, past the new words, to see how the community is growing and deepening it collective understanding for better applications and actions.

One shift I have seen over the last decade, in the environment and development community at least, is the change from training to capacity building, through capacity development to learning. We have seen this evolve in papers, conferences, programmes, departments, and it has even manifested itself in people’s titles. Take mine for instance. In the last 15 years of work (3 different institutions), I have gone from the Director of Training, to Director Capacity Development, to the Head of Learning. And this has not just been in words on business cards only; the way I work and my orientation has fundamentally if gradually changed.

15 years ago, capacity building was mostly about training, it was an extension of the academic environment and the realm of experts imparting useful information on participants and students, whether in a headquarters meeting room, or an extension office. It was for the most part workshop or event-based, intensive, and had lots of reading materials. When it existed, curriculum development was based on university outlines, reading lists and lecture notes, with discussion questions. Models like Train X were used to develop lesson plans for training (now I cannot find any mention of this methodology on the web, interesting). What participants got out of it was ascertained in exit questionnaires, much of it however was not repeated very often. It was focused on what people had to know to do something, starting from the ground up.

Capacity building took over from training, with more of a focus on application and a fuller understanding of the professional in his/her environment. Somehow capacity building was a broader, more integrated concept. Capacity development became the vernacular after about 10 years of building capacity, and with the increasing acknowledgement that professionals brought with them their own capacity, and often LOTS of it. So no longer were we building it (e.g. from scratch – with empty vessel-like connotations) but that we could strengthen and further develop into areas of excellence within people. Capacity development also came out of the classroom to many different in-situ environments – complete with more individualised applications and practice.

This subtle shift began to focus the process on the individual. More needs assessments, better understanding of what the people needed to DO with the information, helped to tailor and refine the input, which was now not only an event, but adopted a longer term approach – and more intervention opportunities – shadowing, mentoring, peer-learning, networking, work-place learning, preparatory e-conferences, post-activity advisory services, etc. And the whole process can be fun.

The newest shift to learning is an interesting one. Now it is all about me (well, not me personally, but all of us). No longer do I necessarily need my own learning and development to be moderated by some outside person or group, or include too much formal instruction, training or otherwise. I may want that for something specific, but I can develop my own pathway for improvement and updating to match what I want and need. Learning can happen anywhere and at any time. As we have read in Jay Cross’ book Informal Learning, 80% of workplace learning happens almost without our awareness – at a Sponsored coffee morning, in meeting discussions, in reading notices posted in the staff toilets, in our web searches, in our evening experiments with Second Life. Now a Learning Director has every spot in and outside the workplace to play with, and practically every hour of the day.

The end result is the most important and it is mostly determined by you, the learner. What do you need to do a great job? What do you need to learn, and what medium (or better, media) works best for you – and how many different, interesting, energizing ways can we help you to gather or create your knowledge, analyse it, test it, apply it, learn from it, and then keep at it. Now its lifelong learning, slowly moving, shifting and changing, just like those tectonic plates.

(Note: This post was inspired by my current reading of colleague Nicole’s “Opportunity Plan” for a leadership programme of ours. Apparently Business Plans are out, now they are called Opportunity Plans – I’m curious about the conceptual shift in thinking that’s behind this change.)

We are here at the World Conservation Congress Forum, which started officially yesterday, One of our activities is coordinating a facilitation team of six who are working on 38 different sessions with session organizers. As this is the first time that we have done this, I thought we would capture some lessons along the way.

We are here at the World Conservation Congress Forum, which started officially yesterday, One of our activities is coordinating a facilitation team of six who are working on 38 different sessions with session organizers. As this is the first time that we have done this, I thought we would capture some lessons along the way.

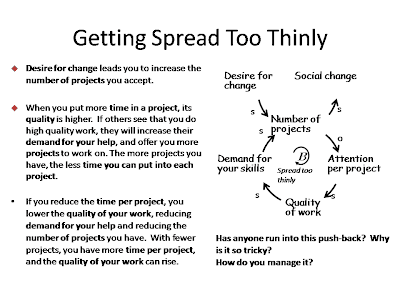

See Doug Johnson’s

See Doug Johnson’s

We have just driven out of Yellowstone National Park, past herds of bison and grazing elk, through Shoshone National Forest along the Buffalo Bill Highway into Cody, Wyoming. My husband remarked that this had been the longest time he had been away from an internet or telephone connection in his professional life (he is a software engineer with a PDA). And I too cannot remember the last time I had five days with absolutely no way of reading my email or checking into the office.

We have just driven out of Yellowstone National Park, past herds of bison and grazing elk, through Shoshone National Forest along the Buffalo Bill Highway into Cody, Wyoming. My husband remarked that this had been the longest time he had been away from an internet or telephone connection in his professional life (he is a software engineer with a PDA). And I too cannot remember the last time I had five days with absolutely no way of reading my email or checking into the office.