At the end of 2024 and onset of 2025 I was happily traveling around India and didn’t make time for an end-of-year reflection exercise. And I think I felt a little less intentional last year as a result.

This year I spent around 8 hours creating a review schedule, having a mini “kitchen table workshop” with a friend, and putting together a guide for the next 2 months. My goal was to create a more considered framework for 2026 – not too prescriptive, but providing a direction of travel, so that I could make good decisions when confronted with inevitable choices. I also aim to schedule quarterly reviews this year to check in with myself periodically, rather than only at the end of the year. This should help me catch things or bend my plans a little based on observations and learning.

These three parts (preparation, workshop and guide development) looked like this:

Preparing to Reflect

In this first part, I created a schedule, designed and printed my simple templates, and put together the beginnings of a notebook to organize my materials. I reviewed the list of my activities the previous year so I could remember them – this involved looking over my wall calendar (year at a glance), and previous year agenda. I put my materials together (markers, post its, etc.) and prepared for the mini workshop.

Holding the Mini Workshop

I wanted to take this seriously, so I invited a friend, made a schedule, blocked the time (3 hours) on a quiet morning over the holiday break. Tea and healthy snacks and a couple of candles helped brighten the space (literally the kitchen table).

Here is the workshop schedule:

******************************************

Annual Review & Reflection (Design for 2 hours and 15 min – Note: It took 3 hours!)

Preparation: Bring your calendar/agenda, notebook and pen. Review projects completed in 2025.

Part I: Presencing & Getting Ready to Reflect

- Coffee and catch up (5 min)

- Agreements: Make the space an oasis. Take a breath. Connect without performance or fixing. Others? (Note: We added positivity and a holding a growth mindset) (2 min)

- Mind Sweep Exercise: Write down everything on your mind right now – what has your attention? The objective is to get everything off your mind and captured before starting. (Template) (5 min)

Part 2: Reflections on the Last Year

- Reflecting on Last Year Exercise: Answer the questions quickly (Template – I used and adapted some questions from the first part of this GTD question list and added some additional ones) (15 min)

- Exchange (what you want to share) (5 min each, listening and no comment – 10 min)

Part 3: Visioning & Planning the Upcoming Year

- Ideal Future: Day in my life on 29 December 2026 – what do I want to say I’ve done this year on this date? How am I feeling? Short narrative writing (5 min)

- Visioning Next Year: Answer the questions quickly (Template – I used and adapted some questions from the second part of this GTD question list and added some additional ones) (15 min)

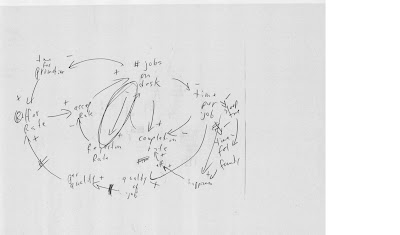

- Setting Contexts Activity: In which contexts (or for what Roles) do you want to set goals for next year? (5 min) (Note: I ended up with 9: Writing, Research, Teaching, Consulting, Health & Fitness, Business Manager/Colleague, Wellness & Mental Health, Being a Good Human, Volunteer/Board Chair, and Homeowner)

- Context Ratings Activity: On a scale of 1 (not very well) to 10 (very well), how happy are you with how you are currently doing in each of these contexts? (Template: Scales) (5 min)

- Goal Setting for Contexts: What is your end-of-year goal for each context? This can be broken down into projects within each context (as desired). Try for SMART Goals: Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound. (15 min)

- Quarterly Milestones per Context: What are the quarterly milestones that you can set that will lead you to the overall goal. Set them for 31 March, 30 June, and 30 September. A3 sheet (10 min)

- Exchange Goals and Milestones: Listen first and then take any feedback (5 min each – 10 min) (Note: This definitely took longer)

Part 4: Strategies

- Ideal Week: Time blocking your ideal/generic week. Write this out on a card. (5 min)

- Exchange (5 min)

- Creating a Weekly Review Checklist: Questions to ask at the end of each week. When and how will this be used? (10 min)

- Exchange (5 min)

- Reflections and Next Steps: What more does this reflection need to make it actionable? (5 min)

******************************************

The above schedule and prompts were inspired by David Sparks and Mike Schmitz of the Relay FM Focused podcast, David Allen’s GTD – Getting Things Done system, and my own tools. I can honestly say that we spent a good 3 hours in our mini workshop and could have used more time. When you do it with a friend who can challenge you gently on some of your assumptions, you need to build in more time for exchange and perhaps some revisions. Thus, the timings above are definitely indicative.

I also noticed that, as I reflected, I increased the number of areas of focus/contexts during the workshop. I might ultimately regret this context inflation, but it seemed right at the time. It also meant that I needed some additional time to develop the quarterly milestones, which took an additional few hours of quiet time that I usefully gained on a long flight after the workshop.

Making the Guide

I’m ultimately an analogue person, so my guide is an A4 Atoma notebook with section dividers (see lead photo). I find this system very flexible and enjoy the “maker” aspect of creating a notebook (hole punch, covers, tabs, rings and all). Because I wasnt to have an artefact that I can use to guide quarterly reviews, as well as my next end-of-year retreat, I want to be able to add pages to build up and capture those incremental reflections, milestones, and learning.

I was determined this year not to over schedule or over plan. This type of dedicated time and focus can subtly encourage that. However, I went into the activity with the intention of gentleness and calmness. Let’s see if a more meaningful end of year close and visioning forward can help me do that.

What kind of creative process produces ideas like a

What kind of creative process produces ideas like a

We have just driven out of Yellowstone National Park, past herds of bison and grazing elk, through Shoshone National Forest along the Buffalo Bill Highway into Cody, Wyoming. My husband remarked that this had been the longest time he had been away from an internet or telephone connection in his professional life (he is a software engineer with a PDA). And I too cannot remember the last time I had five days with absolutely no way of reading my email or checking into the office.

We have just driven out of Yellowstone National Park, past herds of bison and grazing elk, through Shoshone National Forest along the Buffalo Bill Highway into Cody, Wyoming. My husband remarked that this had been the longest time he had been away from an internet or telephone connection in his professional life (he is a software engineer with a PDA). And I too cannot remember the last time I had five days with absolutely no way of reading my email or checking into the office.