|

We’ve recently put together the Balaton Group Book List of 124 books by Balaton Group Members. If you are interested in systems thinking, systems dynamics, sustainable development and related issues, you might be curious to look at this collection, which includes a wide range of titles from academic books to games books.

There are books by the Balaton Group Founders, from the Limits to Growth series to Thinking in Systems and Groping in the Dark: The First Decade of Global Modeling, among others. These are followed by over 100 titles by other Members (single or collective authorship) such as: Image 2.0: Integrated Modeling of Global Climate Change; Tackling Complexity: A Systemic Approach for Decision Makers; The Local Politics of Global Sustainability; Affluenza: How Overconsumption is Killing Us; Creating Regenerative Cities; What if Money Grew On Trees? Asking the Big Questions about Economics; and many, many more…

Donella and Dennis Meadows – authors of The Limits to Growth – founded the Balaton Group in 1982. The Group has met annually for over three decades on the shores of Lake Balaton to advance the boundaries of research and strategy for sustainable development, using a systems perspective. Collaboration among members has resulted in book projects, over a hundred conferences, new learning centres and NGOs and uncounted computer models, training programmes, planning methods, journal articles, films, videos, policy initiatives, educational games, courses and research projects.

This Book List provides fascinating insight into the Balaton Group Members’ considerable work over the years in these issues. We hope this collection helps others interested in sustainability issues find a wide range of thoughtful work in our field. Feel free to share the Balaton Group Book List page!

This is an occupational reality that I need to remind myself about from time to time related to the work facilitators do. The resulting advice that I give myself may also be pertinent for trainers, event planners and staff members with bosses using “just-in-time” management or a firefighter approach to work.

You are invited to join processes when they are very important.

Leaders, teams and organizations invest in external support and help when the outcomes matter greatly – they need to gather information for the next submission of a critical funding proposal, they are bringing all their dues-paying members together for an annual inspirational meeting, once in every five years the Board meets to do strategic planning, they are trying to develop a historic industry standard through a multi-stakeholder process. These events can be milestones in the sustainability of an organization.

What if you, as a facilitator, have all of these things happening in the same month?

Let’s hope that doesn’t happen all the time, but it can certainly be the case that you have two or three big projects winding up very close to one another on your own calendar. Each one heating up in the weeks just before – potentially all at the same time.

It is important, as the Facilitator, to put yourself in the host organization’s shoes and not be surprised when calls run over (maybe by as much as 1.5 hours), when they really want to see you and not just have a conference call, when they are eager to talk through an idea with you even at 11pm at night or on Sunday morning when they are having their last preparatory team meeting. The event you are helping them with might be THE event of the year for them and they will be putting every ounce of effort into it. And they will make many exceptions to make sure it is absolutely perfect, which is great, and will invite you to make them too.

What can facilitators do to manage these exceptions? 3 things immediately come to mind:

- Build in Resilience: This particularly in the form of time. Don’t schedule 15-minute interviews 15 minutes apart, don’t take meetings in 2 cities with only as much time as it takes to get between them in between, etc. Things will go over, they will be delayed because of last minute things on the host organization’s side, they will be postponed because the programme is not quite developed yet, etc. Building in resilience to take these changes (which may be last-minute-before-the-event for them, but be all the time for you, the facilitator) means keeping space in your schedule and in your head to work with these exceptions.

- Husband your Resources: Try to maintain your routine even amidst these exceptions. Eat properly, exercise and above all SLEEP! Don’t wind up going to these very important events with a sleep deficit. This is another way to build in resilience so that too many late nights in a row don’t render you less than your usual creative and calm self. I wrote a whole blog post about this: Facilitators: To Your Health!

- Planning, Planning Planning: And of course, this is perhaps the obvious one, but easy to short cut when you might be contacted late in a process, or when organizations are eager to save funds (understandably in the current global financial climate many sustainability organizations are particularly sensitive to this). This might sound counter intuitive, but more time budgeted for planning and preparing your event can easily mean less time needed for last minute fix-its for mission critical meetings. And again, good planning and preparation will build resilience into your system, because with all the known things planned and organized you can be more open to fielding the unexpected whether before or during the event. And unexpected things will happen – expect them! (These can be rather extreme – I was holding an international learning event with 250 people in Moscow when 9/11 happened, we stopped everything and devoted a full day to dialogue to try to understand what was going on in the world from many international perspectives – from this, to a handful of people losing their luggage thus taking out one of your support staff members for a while to deal with that.)

For those of you who are fans of the FishBanks game, originally developed by Dennis Meadows, there is a new online version that has been created by Dennis and John Sterman at MIT. In this free online version you can play as an individual or part of a class. It can be accessed here: FishBanks Online Version.

I recently ran it twice (in French no less) using the Board game version (in the photo above) and it remains one of my favorite games to play that provides profound lessons about common pool renewable resources management, using systems thinking, growth against limits, and collaboration vs competition.

If you want the Board Game version (which comes with software for your laptop, instructions and all the role descriptions and pieces), you can access it here: FishBanks Board Game Version.

This second link tells you more about the game, how to use it and what kind of learning objectives it reaches, as well as how to order it.

Let’s go fishing (sustainably)!

If you are interested in Systems Thinking, then Pegasus Communications (Systems Thinking in Action – based near Boston) writes the useful Leverage Points Blog. With posts on everything from What it Takes to Lead a “Tribe” to 10 Useful Ideas on Systems Thinking.

One of the posts that caught my eye as particularly practical is their post listing 10 Favourite Systems Thinking Books of the Past 10 Years (or So). I have most of these books, and indeed they are my go-to texts when either learning or helping others learn systems thinking. They range from the technical textbook of John Sterman (Business Dynamics) to story-based learning about systems from Linda Booth Sweeney. From the first person examples from daily life on a farm that Dana Meadows narrates, to the future projections of the World 3 Model as written up in Limits to Growth by Dennis and Dana Meadows and Jorgen Randers.

I wanted to make a note here on this blog to remember this useful list and also connect the article to one of the most enlightening texts on systems thinking that I have found, and is referred to as a classic, which Dana Meadows wrote called: Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in the System. This is a list of intervention points in increasing order of effectiveness – from numbers to mindsets – which creates an incredible checklist for any aspiring change maker.

I wrote in a past blog post about using Appreciative Inquiry to “makeover” the lessons from a great team game called Thumbwrestling. The post was called: Activity Makeover Using Appreciative Inquiry: From STUPID to SMART.

In that blog post I go through in some detail the debriefing, after the action happens (see that post for this info). But I didn’t describe the main set up, briefing and steps of play. I had a request recently to describe the game administration, so I post them here for information.

First of all, I was delighted to find that Thumb Wrestling (aka ThumbWar) is really well described here in Wikipedia. I was interested to read that in some of the chants that are used (by children I guess, I have never heard them in my workshops) the phrase “You are stupid and I am great” is used. It is interesting that we often used (in the past) STUPID as a mnemonic to help understand what structure creates the behaviour of competition (Small goals, Time pressure, Untrusting partners, etc.). In the blog post mentioned above, we used an Appreciative Inquiry approach to make that over into then new mnemonic of SMART or SMARTS.

Thumbwrestling Game

To set the game up, the Game Operator announces that “We will engage in a simple competition called Thumb Wrestling. Everyone needs to find a partner to play”. At that point the Game Operator also finds a partner to do a quick demonstration; someone who has been briefed to demonstrate a rather aggressive style of play. In the demo, you lock hands with your demo partner and tell people that their goal is to “Get as many points as you can.” You inform people that they will have 15 seconds to do this, and then you demo how to make a point by elaborately struggling to pin the thumb of your opponent, warning people not to hurt each other. Ask everyone to keep track of their own points. You then shout “Go!” and time out the 15 seconds, shout out a 2 second warning.

In the debriefing, you can survey how many points people got, and then have the pair with the highest points demonstrate their style, which is bound to be collaborative, based on trust and their ability to ignore norms, models, language, time pressure, and small goals which normally influence people to play this game in a highly competitive way. Now the blog post on debriefing kicks in – so see that for more!

The description above should be enough to help anyone run the game as a team building exercise (again see the previous post for debriefing). If you want a better description with the systems thinking frame, with more precise timing and briefing/debriefing questions, Linda Booth Sweeney and Dennis Meadows have written them up in the Systems Thinking Playbook, which also includes a DVD of someone running all the games so you can see exactly how to administer them.

Happy wrestling!

In February, I had my first “TED-ache” at TEDActive2011. TEDsters know all about TED-aches. They come with the “mind-mash” that is a TED conference. One minute its talks on quantum mechanics, biochemistry or brain science. The next its the latest in information technologies. And then you’re plunged deep into the ocean, taking a swim with seals alongside a nature photographer. Or you’re marvelling as a life-size horse puppet breathes and trots around the stage, and then Bobby McFerrin has you singing and laughing from your gut!

In February, I had my first “TED-ache” at TEDActive2011. TEDsters know all about TED-aches. They come with the “mind-mash” that is a TED conference. One minute its talks on quantum mechanics, biochemistry or brain science. The next its the latest in information technologies. And then you’re plunged deep into the ocean, taking a swim with seals alongside a nature photographer. Or you’re marvelling as a life-size horse puppet breathes and trots around the stage, and then Bobby McFerrin has you singing and laughing from your gut!

This is no ordinary conference. It stretches you to go where you would likely not go if just browsing the talks on TED.com. Most people listen actively to every single talk. And the beauty comes in the meaning you make for yourself as you listen to talks on a great diversity topics and begin to see patterns; to make connections; to find learning where you might least expect it.

On the journey home, I tried to create a mindmap as I read through all my notes (without which I would have retained but the merest fraction of ideas worth spreading). It was messy. However, perhaps even messier still has been my process of trying to sort all my tweets into some sort of coherence in order to share them here. From the mind-mash that was TEDActive, here are what are still a mish-mash of tweets (with some tweaks) to share my take-aways with you, clustered under some imperfect headings. The talks can be found here: TED2011 Talks

a. Perspective

b. Right, wrong and assumptions

c. Unintended consequences

d. The need to encode ethics in algorithms

e. Innovation and counter-intuition

f. Instrumental information: visualizing systems

g. Collective wisdom for change

h. Art for social change

i. Crowd-voicing

j. Collaborative creativity

k. Leveraging learning

l. Breathtaking medical breakthroughs

m. Miscellaneous communication products and technologies

a. Perspective

Astronaute in space Cady Coleman speaks perspective & the importance of connectedness & value of the earth as she circles once/18 mins.

“If a chunk of metal can be in two places at the same time, you could be. We have to think about the word differently as an individual” Physicist Aaron O’Connell.

Physicist Aaron O’Connell: “Everything around you is connected & that’s the profound weirdness of quantum mechanics.”

In a gfa-1 microbe in Mono Lake CA, arsenic seems to function as phospherous in a cell. Evidence of alternative biochemistry on our planet? It would change our definition of habitability elsewhere… Felisa Wolfe-Simon

We can only find what we know how to look for. For Felisa Wolfe-Simon that’s learning to look for alternative biochemistry on earth.

Edith Widder’s eye-in-the-sea explores bioluminescent deep ocean life & language. “Don’t know what they’re saying… I think its sexy!”

Paul Nicklen chokes up recounting leopard seal stories from his polar photo missions for Nat Geog and shows pictures of the white ‘Spirit’ or ‘Kermode’ bear – only 200 left on the planet! Save sea ice; its as important as soil.

Swiss explorer Sarah Marquis: “I dont want to put people back in nature; I want to put nature back in people”. “Let your soul touch the earth…. go walking.”

RachelSussman photographs living things >10’000 years old. “If you didn’t know what you were looking for, it would be easy to overlook something other megaflora were grazing on before extinction”.

b. Right, wrong and assumptions

“Trusting too much in the feeling of being right can be very dangerous and create huge tactical and social problems as we believe our beliefs reflect reality and make huge assumptions to explain people who disagree with us: assume their ignorant, idiots and/or evil, leading us to treat each other terribly, missing the hole point of being human. The miracle of the mind is that you can see the world as it isn’t.” Kathryn Schulz

“We need to learn to step outside of rightness, look around at one another and the vast complexity of the universe and say: ‘Wow, maybe I’m wrong!The system tells us getting something wrong means there’s something wrong with us. We learn the way to succeed is to never make any mistakes.” Kathryn Schulz

“How does it feel to be wrong?” Asks Kathryn Schulz. “Wrong. You’re answering the question, ‘How does it feel to realize that you’re wrong?’ It feels like being right to be wrong until until you realize you’re wrong.”

Daman Horowitz speaks about his work in prisons giving philosophy classes & the importance of questioning what we believe and why we believe it, including exploring wrongness. “What is wrong? Maybe I am!”

Magician Franz Harary demonstrates playing with glitches in peoples minds that distort and manipulate thoughts, using magic to fake technology that doesn’t exist.

c. Unintended consequences

Evolution will be guided by us in the future, thanks to genetics. What will we choose? More competitive? Empathetic? Creative? “If anything had the potential for unintended consequences, this is it!” Harvey Fineberg

We cannot foresee all consequences. But how can we close the gap between capabilities & foresight? Edward Tenner’: “Learn meticulously from unintended consequences & chaos”.

Edward Tenner: An example of unintended consequences = adding lifeboats to a ship, making it more unstable and resulting in tragedy.

“We are at a threshold moment: a single global brain of almost 7 billion individuals learning collectively at warp speed = very powerful and potentially very dangerous. Nuclear weapons are evidence.” David Christian

Looking at ‘big history’ shows us the power of collective learning and the dangers that come with it. Studying this will help all students make better decisions in the future. David Christian

d. The need to encode ethics in algorithms

“We need new info (Internet) gatekeepers to encode ethic responsibility into their (Facebook, Google…) algorithmic code & give us some control” El Pariser.

Speaking of Facebook and Google, Eli Pariser asserts: “’Personalized algorithmic filter bubbles are throwing off balance our info diet, converting it to info funk food.’

“The demise of guys is a consequence of arousal addictions stimulated by the internet & video ‘porning'” – Philip Zimbardo

e. Innovation and counter-intuition

“The greatest time for game-changing innovation was The Great Depression.” Edward Tenner

“When you train people to be risk averse, they are reward challenged”, said Morgan Spurlock in his talk encouraging the embracing of transparency. He sold the naming rights to his talk.

Inspiring talk by Kalia Colbin about reimagining Christchurch: “10 days ago my be the beginning of the demise of my city, but in the rubble their may be promise”. Help with ideas at www.reimaginechristchurch.org.nz.

Do something good for the city and we’ll give you more land, says Malaysia to property developers as incentive. Thomas Heatherwick does, with buildings that leave more ground for the forest.

For the first time in history not one child in Utter Pradesh & Bihar (northern India) has Polio. New vaccine + resolve + tactics = a unique eradication opportunity. Bruce Aylward

Chefs Hamaru Contu & Ben Roche introduce “Disruptive Food Technology”: from the Future Food science lab: tricking taste buds we can reduce energy & waste http://planetgreen.discovery.com/tv/future-food/.

Bill Ford asserts ingenuity in mobility solutions is not only about our movement, its also about access to food and healthcare. Smart cars, smart parking, smart signalling and smart phones all integrated in new smart mobility system is the future.

A leap in thinking is needed to avoid global gridlock if the population reaches the predicted 9 billion in 2044. Real time data is needed for a new mobility system. Bill Ford

“If we sped up cars in our cities by 3mph, we would reduce by 11% the emissions of our transport system.” Counter-intuitive! Luis Cilimingras, IDEO (formerly FIAT)

Speaking of cars actively driven by the blind (unveiled Jan 2011 http://is.gd/ruV8l1): “Technology will be ready, but will society be ready?” Need system change. Dennis Hong

f. Instrumental information: visualizing systemss

“As the world becomes increasingly instrumented and we have means to connect the dots, we can see interactions not previously visible with profound implications for us as individuals” Deb Roy,

Deb Roy set records in home-video hours to reveal patterns linking words to context and identifying feedback loops as his son acquired language in his Human Speechome Project http://j.mp/ePanlq.

Collaborating with scientists, Rajesh Rao tries to use computer modelling to decipher the last major undeciphered ancient script – Indus. Does it boil down to picture of ‘bee’ + ‘leaf’ = ‘belief’?

Ebs and flows in US flight patterns are visualized, providing powerful communication www.aaronkoblin.com/work/flightpatterns/

Carlo Ratti, MIT SENSEable City Lab, uses pervasive technologies to track trash in an investigation into the “removal-chain”. Listening to Haydn’s ‘Farewell’ Symphony (45), he shows us trash doesn’t leave, just moves! http://senseable.mit.edu/trashtrack/

g. Collective wisdom for change

Students tackle 50 interlocking systems problems learn how not to follow short term destructive paths and learn how to think about World Peace long term, learning right and wrong through their experience. John Hunter

John Hunter asserts very openly that the collective wisdom of his 4th grade students is so much greater than his own. He trusts them to solve world problems, practicing with his World Peace role-play game.

US General Stanley McChrystal talks about changes in leadership with distributed technologies and the inversion of expertize as old ‘leaders’ are less familiar wit the technologies required.

h. Art for social change

Under house arrest in Shanghai, Ai Weiwei speaks via video of art for social change & the creation of a civil & more democratic society in China despite no party willingness.

Street Artist JR’s wish: “Stand up for what you care about by participating in a global collaborative art project. And together we’ll turn the world INSIDE OUT”: www.insideoutproject.net

Women Are Heroes project by street artist JR: www.womenareheroes.be In Kibera “we didn’t use paper (on the rooves), because paper doesn’t prevent the rain from leaking in the house but vinyl does.”

“It doesn’t matter today if it’s your photo or not. The importance is what you do with images… We decided to take portraits of Palestinians and Israelis doing the same job. They all accepted to be pasted next to the other.” JR

i. Crowd-voicing

Human right activist & TED Fellow Esra’a Al Shafei presents www.crowdvoice.org – a project of MidEast Youth tracking voices of protest around the world using crowdsourcing.

Wael Ghonin: Egypt saw extreme tolerance, Christians & Muslims protecting one another praying. “The power of the people is much stronger than the people in power”.

Surprise talk by Wael Ghonim on the Egyptian revolution: “No one was a hero because everyone was a hero.”

“We cannot have a well-functioning democracy if there is not a good flow of information to citizens” El Pariser.

Head of Al-Jazeera, Wadar Khanfar: “The democratic revolution sweeping the Arab world is the best chance to see peace. Let us embrace it.”

j. Colloborative creativity

“Electronic communication will never be a substitute for someone who face to face encourages you to be brave and true” Marc Martens talking of the powerful “Glow” public art playground http://glowsantamonica.org/. Public art to connect people is at the heart of the Santa Monica ‘Glow’ project.

Face ache follows the Bobby McFerrin session. “Unparalleled joy” was in the programme! Playing along with Bobby’s creative spontaneity warmed everyone’s hands, voices and hearts.

The lennonbus.org at #TEDActive – a non-profit mobile recording studio dedicated to providing students with opportunities to make music and video projects.

eyewriter.org – an ongoing collaborative research project using completely open source technology to empower people suffering with paralysis to draw with their eyes. Mik

Co-creating a music video through crowdsourcing: Aaron Koblin describes www.thejonnycashproject.com: a living, moving, ever-changing portrait as people all over the world contribute portraits to the collective whole.

Aaron Koblin: “Interface can be a powerful narrative device”, showing a crowd-sourced video, which when viewed is unique to each viewer www.thewildernessdowntown.com/

Conductor Eric Whitacre’s “Lux Aurumque” gives voice to a virtual choir – http://ericwhitacre.com/the-virtual-choir. The upcoming project received >2050 videos online from 58 countries.

k. Leveraging learning

Project V.O.I.C.E. – lovely project by Sarah Kay uses poetry as a way to entertain, educate & inspire. List 10 things you know to be true. Sharing these lists – who has the same? / opposite? / who heard something never heard before? / heard new angles on what you thought you knew? Sarah Kay

Make a list “10 things I should have learned by now.” Sarah Kay uses poetry to work through what she doesn’t understand with a backpack from where she’s already been.

Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio looks at the conscious mind: “There are 3 levels of self: The proto, the core & the autobiographical (past & anticipated future). We share the first 2 with other species.”

NYT Columnist David Brooks asserts emotions are the foundation of reason and, as social beings emerging out of relationships, we need to learn better how to read, listen to and talk about emotions.

Ed Boyden explores the brain signals that drive learning & describes the process of installing molecules in neurons and using light to turn on/off specific cells in the brain and treat neurological disorders.

“Personal perceptions are at the heart of how we acquire knowledge.” Autistic Savant, Daniel Tammet, shares insights from synaesthesia about colours, textures & the emotions of words & numbers.

29% greater retention from doodlers & better problem solving because it engages all learning styles – Sunni Brown. “The doodle has never been the nemesis of intellectual thought. In reality, it’s been one of its greatest allies.”

Khan Academy learning: self paced, interactive, peer-to-peer, encouraging trying & failing (like falling off a bicycle), and designed to be iterative and so avoid ‘swiss cheese’ gaps in education. Salman Khan

“By removing the one-size fits all lecture from the classroom, these teachers have used technology to humanize the classroom.” “What we’re seeing emerge is this notion of a global one-world classroom.” Salman Khan

“Kids 1 year from voting age don’t know butter comes from a cow. They’re not stupid. Adults have let them down. Every child has the right to fresh food at school & food education as a requirement. It’s a civil right” Jamie Oliver

Jamie Oliver’s exciting new announcement about the future of the Food Revolution: http://bit.ly/hbRmGM #TED

Alison Lewis presents fashion technology, encouraging DIY “Switch Craft” projects blending sewing and electronics to bring handiwork into the 21st century: http://blog.alisonlewis.com/?p=541.

Fiorenzo Omenetto reinvents something that’s been around for millennia. Learning from silk worms, he reverse engineers the cocoon turning water & protein into material with environmental & social significance.

A seed cathedral, inspired by Kew’s seed bank, jurassic park & play doh mop-tops is Thomas Heatherwick’s stunning London Pavillion @ Shanghai: www.heatherwick.com/uk-pavilion/.

Learn a second language in Second Life: an alternative emersion process that works with the 5 stages of second language acquisition and the mastery of the 4 language skills, says Jeong Kinser.

Indra Nooyi talks about Pepsi’s Refresh University to sustain & multiply social change emerging from www.refresheverything.com: stories, lessons & ‘how-to’ online + leadership skills training.

l. Breathtaking medical breakthroughs

Luke Massella is living proof of Anthony Atala’s regenerative organ work. He was one of the first ten people to receive a ‘printed’ kidney. 3D printed organs are the next frontier in medicine.

Eythor Bender showcases his incredible exoskeletons, which enable the paralyzed to walk again.

m. Miscellaneous communication products and technologies

The effects of HIV can be reversed. Watch this powerful ad from the Topsy Foundation: http://t.co/lLph2Or via @youtube.

A compelling video for the genocide-awareness www.onemillionbones.org/ project by Art Activist TED Fellow Naomi Natale #TED: http://youtu.be/FFukmsLLG0k.

Weforest.org’s “Lessons from a tree” video – narrated by Jeremy Irons – supports the “Buy2get1tree” campaign, working with corporate partners to save 2 trillion trees by 2014. Bill Liao

Kate Hartman creates devices that play with how we relate and communicate with ourself, others and nature. “Our bodies are our primary interaction with the world”.

The Handspring Puppet Company breath life into a larger than life War Horse puppet on stage using masterful “emotional engineering” and “up to date 17th century technology to turn nouns into verbs”.

Mike Matas demos www.pushpoppress.com/ – the first feature length interactive book and sequel to “Inconvenient Truth” – with Climate Change solutions. Blow on the screen to turn wind turbines!

A smart braille phone varying the height of a pixel instead of color to communicate information on “screen”: A concept of TED Fellow – SumitDagar.com.

Mattias Astrom demos C3, a new 3D mapping technology: http://www.c3technologies.com/

Bubbli – ambitious new startup seeks to change the way we record images with cameraphones. Terrence McArdle & Ben Newhouse.

Shea Hembrey invented 100 artists and imagined their art. http://www.sheahembrey.com/

I am currently working with a team focusing on biodiversity conservation and assessment to “makeover” an existing training curriculum into one even more interactive and learner-focused. As a part of this process I offered to put together a selected list of resources, from the raft of those available, that are particularly useful to me in this kind of work.

As trainers, capacity developers, learning practitioners, and facilitators we have before us a veritable sea of interesting tools, techniques, and even toys that have been developed to help make our events successful and enjoyable (yes, we have discovered a learning space where we can have fun and learn at the same time!)

Because this sea is vast, we each have our own parts that we prefer. And our selection of what we bring with us may be different every time – we might dip in and out, or we might dive deep into one area or another. It’s always varied, to keep both us and our co-learners fully immersed and engaged. What follows are some of the places I go to find inspiration (many I have written about on this blog and in these cases I will link up the posts or the tag).

Of course I always approach an event from the point of view of its learning objectives. Once those are clear, how you achieve these is an exercise in building an agenda or process that will, as much as possible, bring people out of their everyday discussions into a vibrant learning zone. Try…

Games

I use “games” frequently in my learning work, whether they are quizzes (see: Want to Learn More: Take this Quiz), experiential learning processes (see: An Appetite for Experiential Learning), or introduction games (see: An Amazing Group of People), or others. I find they help tap into the natural curiosity of learners and participants. I have written quite a bit about using games (see the tag: Games), and I frequently use the Thiagi Gamesite for ideas and for ready to use games, as well as Thiagi’s books, such as this one on interactive lectures, for when you can’t avoid a presentation. I adapt games, create new ones (see: Make a Game Out of Any Workshop Topic: The dryer the better), and get ideas from other trainer’s games. Brian Remer and The Firefly Group have a nice website and Games newsletter called the Firefly News Flash, for example. I also use the games of Dennis Meadows, such as Fishbanks and Strategem in my work, as well as the Systems Thinking Playbook (NB: We are writing a new Systems Thinking Playbook on Climate Change right now that should be published by GTZ in the next months.)

Discussion and Co-creation Techniques

There are so many wonderful tried and tested techniques and processes available now with which people are getting more and more comfortable (facilitators and participants). I’ll list a few of these here along with some of the blog posts we’ve written about our learning using them. What is also intriguing, once you get really familiar with them, is to mash them up! This helps them be even more suited to the particular needs and interests of your group. Among these is Open Space Technology, developed by Harrison Owen which has a whole community (OpenSpaceWorld) of connected users (see: Opening Space for Conversation (and Eating Croissants)). We have enjoyed learning about and using World Cafes (see: Our World Cafe: Kitchen Table Conversations for Change), and this methodology has also gone global with a useful website (TheWorldCafe) full of its own tips and resources. We have built numerous Conversation Cafes – into our sessions (instead of holding them in cafes). These are slightly different than World Cafes – they are hosted and build conversations without people moving tables.

Specialisations to Add

Storytelling

To a good interactive learning base, you can add some special features to your event (warning: with too many it starts to become full sensory overload). The selection also depends of course on your goals and objectives. What about Storytelling (see: My Point? To Be a “Story” there Must be a Point)- story circles, featuring cases as stories, etc. Anecdote from Australia has a wonderful website showing how you can “put stories to work” and a good newsletter by the same name. Check out their learning White Papers for interesting applications and how to’s. We also have a tag on Storytelling on this blog.

Improv Comedy and Theatre

I love the idea of adding Improv comedy or Theatre activities, especially if you are working in leadership, presentation, conflict resolution, teambuilding or just to spice things up and get the group thinking more creatively. I have been to a couple of Improv Theatre application workshops and have experimented with adding this to events (try to go further than role play.) (see: People Buy Adjectives). John Cremer gave an excellent workshop at last year’s European IAF Conference on using Improv and his website gives more ideas about how to use it for creative thinking and presentation skills learning. If participants need to give presentations as a part of their learning event, why not start with a little interesting improv training on this?

Visual Facilitation

There is a great deal of nuance here around graphic facilitation, visualisation, graphic recording etc. which I lump together as “visual facilitation”. The bottom line is that real-time visuals are created to capture the discussion and activity threads of your event. (see: Making Memories: Improving Your Impact Through Visualisation, Slam Poetry and More). We have worked with a Danish-based group called Bigger Picture, who are members of a larger, global Visual Thinking community called VizThink. We have contributed to visual murals at Society for Organizational Learning Conferences, worked with cartoonists at several IUCN events, all with great results, tapping into visual learners, and giving an extra dimension to our work. Visual facilitation works best when time is given in the session to have participants co-creating, developing personalised icons and talking through what is being visualised.

Systems Thinking

This is one of my personal passions – using systems thinking tools for learning. We have experimented a great deal in applying an approach that might initially appear to be too complicated to introduce in a short workshop. It does have a specialised vocabulary, a number of graphic tools and a set of conventions. We have a tag on this blog devoted to using systems thinking (see: Systems Thinking) which features posts on using it for strategic planning (see: Building Capacity in Systems Thinking: Want More Amplification? Don’t Call it Training), and exploring ways to help learners pick it up and use it in experiential ways (see: Working With Systems Archetypes in Learning Contexts). Systems thinker Linda Booth Sweeney has an interesting site devoted to systems thinking learning and storytelling, and has developed a useful systems thinking resources room.

And So Much More

You can actually find inspiration all around you for making your learning events more meaningful, more engaging, more powerful. Look everywhere (see: When I Was a Game.) Why not do your reporting back after group work borrowing from the current trend in micro-lit? (see: Micro-Lit: Too Wordy, Try it Again or the longer Trendspotting: Micro-Lit and Other Applications) or have all your presentations time in at 6 minutes and 40 seconds because they are given as Pecha Kuchas (see: Taking the Long Elevator – 13 Tips for Great Pecha Kuchas). This great technique helps speakers get to the point by putting all of their inputs into 20 slides, auto-timed at 20 seconds each. Presentations in general can have a myriad of formats – even PPT can be replaced by Prezi (see: Preparing a Presentation? Read this Praise for Prezi) or any other number of innovations (see: The End of Boring: Borrowing, Adapting and Mashing for Facilitators).

Send your working groups on a walk, use the cafeteria or hallway for a session, make cool job aids (get inspired for your handouts by David Seah’s Printable CEO series.) Pull one of your main presentations up into a webinar (see: Look Behind You! The Webinar Facilitator’s Non-technical Checklist), or instead of a live speaker, find an excellent TED Talk video which presents the content in an engaging 15 minutes (see: On My Way to TEDGlobal).

Through this process you will “Learn how to speak agenda” and will be able to both design for interest and impact, and also to write up your agenda like it was a menu at a restaurant. Think of yourself as a diner, if you got this menu (agenda), would you want to eat at this restaurant (or attend this workshop?)

And Finally (although I think this beach is endless)…

A recent book by the World Bank called The Black Box of Governmental Learning, which I am reading right now (download it for free from their website), starts with an interesting history citing the progression of learning in this domain -governmental- although I find it widely applicable from my experience. It talks about the change from expert-driven learning which is lecture-based with limited interactivity, to the newly evolving paradigm of learning with each other. The tools and techniques that I list above can help makeover a learning event from a one-way teaching model, to one where everyone jumps into the topic together.

Such a long list might seem indeed for a trainer or facilitator like jumping in at the deep end yourself, and yet you can wade slowly into this sea of interesting learning tools and techniques, until you find your own favorite place(s). Good luck! Fellow trainers and facilitators, please add your favorites in the Comments section below!

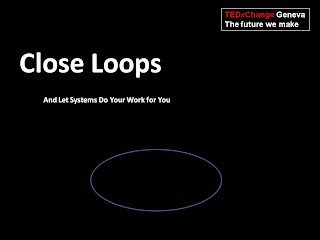

Where do we stand in the work to save and improve lives around the world? What changes have taken place in the last decade? What does the future hold? Listening out for some learning for the future, here are some highlights I took from TEDxGeneva’s TEDxChange event: The Future We Make.

1. Learn to save lives. Learn from a local innovator, a barefoot entrepreneur, a world leading corporate giant. Learn across sectors and scales. Look, listen and learn closely. “Success is relevant because if we analyse it we can learn from it and then we can save lives.” (Melinda Gates)

2. Bye bye linear, hello loops. Take time to understand the system you’re operating in. Create feedback loops to achieve your goals, leveraging energy from throughout the system so it’s not all on you. (Gillian Martin Mehers)

3. Be one step ahead: Diagnosis pays. Never mind the naysayers. Invest in investigation. Don’t stop at symptoms. Diagnose your enemy. Minimize medication (scale up tests and the need for antimalarials drops – see Senegal). Resist fuelling resistance. Eliminate malaria. (Rob Newman).

4. Warmly welcome the wonderful world of statistics. Let data be your guide. And keep it modern, refreshing concepts as you go along. (Can we really still call a country – Singapore – with one of the lowest child mortality rates in the world “developing”?) (Hans Rosling)

5. Bowl in the light. Demand real time data. Turn the lights on. You need to see the skittles and know the score so you can decide on your ball, approach and spin. (And you need to know whether you’re hitting the skittles in your intended lane or next door!) (Melinda Gates)

6. Make a smart entry. You’ll make little progress reducing the strain on natural resources with family planning until you’ve figured out infant mortality. Suss out the system first. Identify the obstacles to change. (Patrick Keenan).

7. Change with children. Children are the Revolutionary Optimists of Calcutta slums. They are the educators and group leaders. “It is our duty – our little brothers and sisters,” they say as they champion and double Polio immunisations, carrying fellow children to clinics. (The Revolutionary Optimists)

8. With women and girls too. Look at Malawi. “Women and girls will lead social transformation.” (Graça Machel)

9. Up the ubiquity. Take a master class from the ubiquitous. Learn to get everywhere from Coca Cola (who serves the equivalent of every man, woman and child on the planet a glass of coke a week) and Thai condoms. (Mechai Viravaidya)

10. Parle local. Be aspirational to beckon new behaviours; avoid avoidance messages. Even if people need something, you still need to make them want it. Take toilets in India, for example, and match them to courtship. Remember, “No loo, no ‘I do’”. (Melinda Gates)

11. Promote promise. Polio. 99% reduction in 20 years. We’ve come so far. How amazing would it be to eradicate this disease?! We can overcome Polio and make it the 2nd disease ever to be wiped off the face of the planet. (ibid)

12. “Aid-u-tain”. Play snakes and ladders (“Auntie takes her pill in the morning when she wakes up. Very good. Up the ladder you go.”) And let the Olympics save some lives (“why just run around?”). (Mechai Viravaidya)

13. Involve everyone. Empower the people – from policeman plod and cabbies to vendors in local corner and coffee shops. “Would you like a condom with your cappuccino?” (ibid)

14. Ever-re-design you. One designer candidly speaks of his purposeful and personal trajectory to maximize impact, ever re-designing his design career. What are you doing to maximize your impact? Reflect on re-designing your career to leverage more change in the system. (Patrick Keenan)

15. Encourage for the cause with networks. Change making needn’t be lonely. From the power of one to the power of many: network your knowledge and scale up confidence, assurance, courage, commitment and even career change. (Cheryl Hicks)

16. Converse. Conversations matter. Talk about action, however small. “We’ve got the future in our hands, lets build it in our minds.” (Bajah and The Dry Eye Crew).

Systems Thinking Learning: Stand Alone or Integrated?

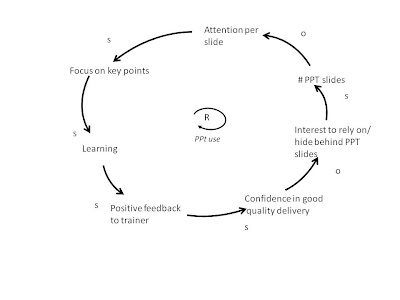

This year I have been working with LEAD Europe (Leadership for Environment and Development) to integrate systems thinking effectively into the leadership curriculum. Last year, I contributed a stand alone module to the LEAD Training (Using Systems Thinking: How to Go from 140 PowerPoint Slides to 2), and think that this year’s more integrated and incremental approach is much more effective, not least because with case-based training you have real content to use as examples and group work.

This year, in the first of the two LEAD Europe week-long training sessions, I introduced the overall concept of systems thinking, and two diagramming tools – Behaviour Over Time Graphs (or Reference Mode Diagrams), and Causal Loop Diagrams (or Feedback Loops). And we used lots of systems games to illustrate the points, I even created a new one called the Flash Mob Game.

The second LEAD Europe session just finished in Brussels earlier this month, and during that week the systems learning focused on Systems Archetypes. This is the first time I have gotten that far with systems thinking learning with a group, usually I only have time to get through the diagramming tools, so it was learning for me too!

10 Systems Archetypes and Where to Learn More

There are some very good resources about systems archetypes. I really like this paper by William Braun titled, The Systems Archetypes, and the online resource Archetypes: Interaction Structures of the Universe by Gene Bellinger to list two. These ended up being good references for the work that groups would be doing on this topic.

I could not imagine anything harder to understand and do something with, than me standing up for 1 hours and giving a lecture about the most common systems archetypes. According to Braun and Bellinger they include (sometimes the names differ slightly):

1. Limits to Growth (Limits to Success)

2. Shifting the Burden

3. Drifting or Eroding Goals

4. Success to the Successful

5. Escalation

6. Fixes that Fail

7. Growth and Underinvestment

8. Tragedy of the Commons

9. Accidental Adversaries

10. Attractiveness Principle

These names are intriguing, seem simple enough, although not completely self-explanatory. Still, using an hour of time to go through them, their generic structures, examples, and the insights thay they give sounded too passive and abstract to be useful to the learners.

Using Peer Learning, Even for Complex Issues

Over the time I had worked with this interesting cross-sectoral group of LEAD Associates, I had seen them to be real self-starters, and still maintaining a helpful stance towards one another. We had worked hard to create a collaborative co-learning space in this programme (rather than a competitive environment). So instead of “teaching” on this issue, I decided to support them as they made these archetypes meaningful for themselves. I started by giving a brief high level overview (e.g. what are they and why they can be helpful). To reinforce the message about paradigms, mental models and habits -which may hinder you from seeing the systems around you – I used 3 short systems thinking, experiential learning games (Colour/Flower/Furniture: See post How Deep Are Your Neural Pathways?), Pens, and Arms Crossed (watch Dennis Meadows run this game in the video Change is Difficult.

Then I put people in six randomly assigned (e.g. pick a card) groups, gave them some background resources, a flipchart template to fill in (see above photo), and had them pick a slip of paper with one of 6 of the archetypes written on it out of a hat. The groups were then given 45 minutes to create their own description of the archetype, give some examples of where they have seen these patterns in real life (including the context of the full-day simulation that we would be conducting on Day 4 of the training), give some insights about what one can do when you spot this particular pattern or archetype, and finally draw a Causal Loop Diagram that illustrates the concept. Each group then picked the name of an archetype out of my hat and that was their archetype for this exercise. They went outside and went to work.

What ensued was really peer learning and team learning: They used the handout resources, explored understanding, corrected any language or comprehension mis-matches, and told stories as examples from their own experience as well as from the case study of this module (the EU carbon emission targets) which was also the basis for the simulation.

When they returned to the plenary, they presented their archetypes and then answered questions/comments from the group, their peers.

When we started, no one had any experience with systems archetypes. However, by the end of this session (2.5 hours) they had a very deep understanding of one (and how it worked, and where it could be useful), and a good understanding of the others, as they listened and talked to their different peers presenting the explanations. For them, I am convinced that this was much better than sitting in chairs and listening to me talk and show them slides of 10 of the most common archetypes. In this scenario, they would not have had the practice identifying and using them.

Using Systems Archetypes

When I designed this session – self-taught systems archetypes – I wondered if it would work. I was pleased that it worked so well – the examples were excellent, the whole thing was personalized, and I could simply intervene to add stories or correct things, as needed. I had time to help groups that might have been stuck, and question them in ways that would get them to think about the issues at a different level.

To reinforce this learning later in the week, I offered a prize for anyone who used or referred to a systems archetype within the context of the simulation. Interestingly, I found many examples of how systems and the archetypes were being used. As a reminder of our archetypes, we kept all the flipchart explanations/diagrams in the room for the rest of the week.

I could have made up a job aid that described in that way all the archetypes, and simply presented it. But this way, the self-taught approach – with participants making their own set of personalized “job aids” for future use – turned out to be an extremely effective way to transfer messages and learning about systems archetypes.

I was very honoured tonight to be able to speak after Melinda French Gates, Graca Machel, Hans Rosling, and Mechai Viravaidya at the TEDxChange event, hosted by the Gates Foundation. Well, this is technically true, although I was speaking on the TEDxGeneva local stage, which followed directly after the simulcast of the New York event.

Lizzie, representing tonight the Hub in Geneva, curated the event brilliantly. It started with the simulcast, a break and then four local speakers including Dr Robert Newman, a pediatrician at World Health Organization and Director of the Global Malaria Programme, Cheryl Hicks an independent business advisor in Geneva who spoke about the power of networks using CSR Geneva as an example, Patrick Keenan – one of the co-founders of the Movement, and me.

I spoke about the power of systems thinking to help social change agents be even more powerful. How can we use the systems around us, close up feedback loops, and get systems to “do our work for us”? During my short talk (10 minutes!) I adapted a demonstration game called Living Loops, from the Systems Thinking Playbook. I used the game to demonstrate the difference between relationships that are linear and take an enormous amount of effort to change, and between systems that have feedback loops that are self-sustaining and can help you reach your goals.

The game helped me tell the story of my brother-in-law, who is working in Mutale in the Northeast of South Africa, and his community’s efforts to start, among other things, a tomato growing business for income generation. When childcare issues threaten to challenge the sufficient engagement of the local labour force to make the business work (many families are run by a single head of household due to absentee parents working in the nearby mines), connecting the profits of the tomato business with creche management and maintenance helps to make this initiative self-sustaining – it satisfies the community’s desire for income and parent’s desire for secure and quality childcare while they work. We played the game demo using a tomato picked from my garden instead of a ball.

After hours of preparation, it’s over now – whew! I enjoyed speaking at the TEDx event, although the quality of all the TEDTalks are so high, that it was extremely nerve wracking to prepare for and then to walk on that stage in front of 100+ people at the University centre in Geneva. We had one of 82 of the parallel TEDxChange events globally, all focused on the 10th anniversary of the Millennium Development Goals and The Future We Make. Big topic, big event, big night – just coming down off of my endorphin rush, and happy I did it!

We started our annual Balaton Group Meeting this morning (held this year in spectacular Selfoss, Iceland). Our topic this year is “Food Futures” and we have already heard several speakers on the topic, including Karan Khosla (Earthsafe in India) who presented a systems model aimed at conceptualising the issues. John Ingram from the Environmental Change Institute (Oxford) shared with us some shocking facts like 15-50% of all food that is grown is lost between the field and the plate. With him we explored the suggestion that alleviating food security by reducing food waste is much cheaper and more environmentally sustainable than just increasing food production. Other Balaton Group Members wondered what reducing waste would do to the GDP (the growth of which might depend somehow on this waste) – an efficiency and resilience discussion will follow in our afternoon Open Space workshops.

We also had 2 brave Pecha Kuchists on the topic: Laszlo Pinter, formerly of International Institute for Sustainable Development and now at Central European University on gathering agri-environmental evidence through an indicator process with OECD. Andrea Bassi from the Millennium Institute was the second, speaking about the agricultural aspects of UNEP’s Green Economy Initiative.

We are currently in discussion and some very interesting ideas have come up, particularly sparked by a presentation about soil by University of Iceland Professor Vala Ragnarsdottir. She noted that currently soil erosion is 100 times faster than soil formation – and suggested that soil is a finite resource.

A systems map showed that the interactions of soil, people and food depend also on oil and mining (phosphorous). When these resources are gone/limited, what can soils deliver themselves and what can they recycle?

This brought up a few observations, such as the notion of “Peak Food”, mentioned by Alan AtKisson, which sent shivers down our spines.

Our Thai Balaton Group member, Professor Chirapol Sintunawa, noted that Iceland is importing topsoil from around the world every day (through importing food from countries such as his). This took us into a discussion of the notion of “embedded soil” (as opposed to, or in addition to, embedded or embodied energy in the lifecycle of goods). Could this be a new part of the accounting methodology that helps people make decisions around use of goods?

Oh, the Balaton Group – an annual opportunity to disrupt our paradigms and challenge our mindsets, and be with old friends who feel the same way.

I just finished co-facilitating a week-long leadership training course with LEAD’s Edward Kellow. Systems Thinking was one of the cross-cutting skills components, which started with an introduction on Day 1 (introduction and drawing Behaviour Over Time Graphs), and then on Day 2 we got into reading and drawing Causal Loop Diagrams. Both were entirely based on a case study which we would be exploring and visiting later that week – in this case the London 2012 Olympics and its sustainability legacy (See Towards a One Planet Olympics). I had introduced systems thinking in the previous year’s LEAD programme – See a previous blog post about: How to Go From 120 PPt slides to 2! I think this year’s approach to spread it throughout the week’s curriculum was even better. ) This game helped us pick it up even at the very end.

We had worked throughout the week in so many different groups and constellations, from Digital Pairs (everyone was given an unknown partner before the workshop to introduce to the group the first night solely from online research into their Digital Identity), to Learning Trios, Presentation Groups, Daily News Groups and LEAD Associate Project Groups. To tie this together with systems thinking, to make visible these interconnections and to celebrate this work, I designed a new game for the closing, called the Flash Mob Game.

We had played the Systems Thinking Playbook Triangles Game earlier in the week (where people stand equi-distant between two people who act as their reference points), and had explored how to spot systems around us, and to harness their inherent energies to help us meet our goals. So rhis new game was designed to play at the end to pick up those points, and to let people “close” the meeting in a fun way. Here is how the game goes:

Flash Mob Game

About this Game:

This game is perfect at the end of a longer workshop, or at least one that has given participants an opportunity to work in a number of different kinds of groups. It is an interesting way to make visible the invisible connections that people have made over the course of the workshop. It also shows how something that from the outside seems chaotic, actually has a number of complex inter-relationships that only become obvious when needed, and over time (at least over the time of this game). Like a Flash Mob, the minute before and the minute after their inter-relationship becomes apparent, this seems like a normal crowd of unconnected and unrelated people.

Time Needed:

10-12 minutes

Space Needed:

An open space big enough for people to walk around in without bumping into things (can be inside or outside, we went outside).

Number of People:

From 15 to 50.

Equipment and Materials:

A bell or whistle (I prefer the softer sound of the bell).

Steps of Play:

- Ask participants to move to the open area to brief the game.

- Briefing: Tell people that they will be walking around on their own in the open area, and periodically stopping on your signal. They can walk anywhere they want and should keep moving without bumping into anyone (or anything!) While they are walking they should remain silent. Upon your signal (bell or whistle), they will stop, listen, and follow your instructions. When they hear the bell, they will start walking silently again.

- Ring your bell and ask people to start walking.

- Let them walk around for a minute, gently remind them not to speak if needed. Watch the group, this random milling around is somehow very beautiful.

- After a minute, ring the bell, and say the following, “Please go find your Digital Partner (pick a group in which they worked that week), say ‘Goodbye’ and tell them how much you enjoyed working with them this week.”

- All of a sudden people will go from a random place into a small group and start to talk. Give them a minute to say their goodbyes and a few words, and then ring the bell again. At this point they melt back into a meandering crowd, and start to walk again. Again wait a minute, and then ring your bell. This time say, ” Please go find your Learning Trio (or Presentation Group, or Daily News Group), say ‘Goodbye’ and tell them how much you enjoyed working with them this week.”

- I use the chronology of the workshop to call the groups, it just so happened that they started as Pairs, went to Trios, and then larger and larger groups. For the final group, I asked people to find their LEAD Associate Project Group, which was a newly formed group that would last for the duration of the 3-module programme. This time I told them to, “Find your LAP Group, say ‘Goodbye for now’ and tell them how much you are looking forward to working with them in the future”. Note: If you do not have any group or activity that continues after your workshop, you could say “Find all your fellow workshop participants, say ‘Goodbye for now’ and tell them how much you are looking forward to keeping in touch with them in the future”.

- After the final Goodbye, ring the bell and let the crowd start to walk again. After a few seconds, end the game and stop for a few words of debriefing.

- Debriefing: If this is at the end of the workshop, you might use it to reinforce some of the systems messages with a statement or observation about how if people outside could see the crowd walking they would never know what kind of interconnections there were in this group, what they have done and what they can do together. If it is earlier in the programme you can ask people to notice the different action at different time frames (random movement and purposeful groups). It is interesting to see how what might look like a number of interconnected people (things, ideas, etc.) might actually be connected in surprising, and potentially useful ways which you can understand if you observe the system carefully over time.

Variations

You could probably adapt this game to a mid-session time frame, or earlier in the workshop if you can identify different interconnections and inter-relationships between people and are sure that they are also aware of them. For example after introductions on Day 1, you could call it the Hello Flash Mob and ask people to find others who work in their sector, who come from the same country/town, etc. and say ‘Hello’ and tell them how nice it is to meet them. This would also help visualise a “crowd” self-organise and then melt into a crowd again. At the end of this version, you could ask them to find the people who are happy to be here, say ‘Hello” and tell them how much you are looking forward to working together this week/day/etc. I would still end with a bell and letting them walk away again. Then stop and debrief the game (as above).

Make sure you test it yourself, we just played it for the first time yesterday (and it worked beautifully)!

Just for fun, here are some of my favorite Flash Mob Videos: Central Station Antwerp, Grand Central Station New York

and Liverpool Street Station in London:

It is far too easy to fall out of reflective practice when you get extremely busy. Like funding for learning, it might be one of the first things to go when resources get tight (at both the institutional and individual level).

It is far too easy to fall out of reflective practice when you get extremely busy. Like funding for learning, it might be one of the first things to go when resources get tight (at both the institutional and individual level).

Then you don’t take the time to stop and think how you can do things better (not to mention why you are doing them and even if you should be doing them.) This can result in incredible ineffeciencies, not to mention actions that can create even more work and take more time because they have not been carefully considered. I queried this in a former post (Is Progress Made By Making Mistakes) because in addition to creating ineffeciencies, errors can come from not taking the time to think through your actions (e.g. putting petrol in your diesal car tank). These can in turn create more work for you, making you even more busy in the long run, with even less time available to think.

When we get busy we sometimes think that we can make progress by brute force, by throwing all our weight and muscle into something. If we want it enough we can just work as hard and as long as we can to make it happen. Then you get stuck in “doing mode” and can’t stop.

The smart alternative, of course, is to stop and create space for reflection to help us identify those ineffeciencies and change our behaviour, change our surroundings, change the rules, change our system, so we can achieve our goals with less effort. But you cannot identify those points of leverage unless you can stop long enough and get up high enough to see the patterns.

You might need some tools to do that. This can be quite personal. Writing this blog helps me organize my thoughts, and when I get busy I really have to make myself write (asking myself “What am I learning?” or “What am I noticing?” or any number of other start questions, and then recording my response.) Other people write in physical journals, or they create images, stories or even songs that synthesize; tools from systems thinking can also help people reflect on dynamics and explore change scenarios when looking for guidance on what to do differently. There are also many kinesthetic techniques to support reflection. It doesn’t really matter which, just pick one.

You can get too busy to think. And if you stick to that too long, you will even get too tired to think. And then, watch that car at your next fill-up.

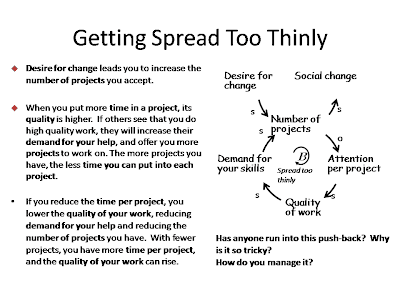

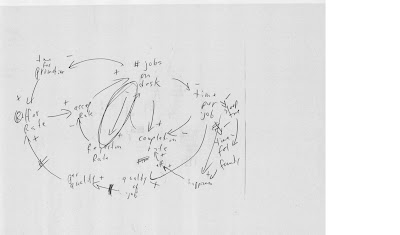

Drawn on a napkin during a recent dinner I had with a systems expert, you might have to look closely to see what this Causal Loop Diagram (CLD) advises. It considers some of the dynamics involved in working independently and wishing to balance work with family life. (Click on the image to enlarge it.)

It connects incoming work and project outputs, time for promotion and what you charge, and the rate of acceptance and completion of jobs. Central to this CLD is the link between reflection rate and number of jobs on your desk – the advice: make sure you always have enough time per job for reflection, and use that time frame as a filter to accept or decline a job (circled link in the centre of the diagram). It is tempting to be flexible on this when you are independent, but the knock-on effects of not paying attention to this important aspect can affect your quality, offer rate, time for family and happiness. A big conversation for a very small napkin…

Can you imagine getting an invitation to a workshop that has as its main goal playing 20 games? Would you go?

Those invitations went out a few weeks ago, and we had a very good response to a test workshop we held in Bonn aimed at playing and discussing 20 games that deliver messages around climate change, using systems thinking concepts.

Dennis Meadows, Linda Booth Sweeney and I have been working together for the last few months to take 20 games from the original Systems Thinking Playbook, written by Linda and Dennis, and adapt them for climate change learning. That process is more complicated than you would think! We each have 6/7 games we are working on, originally selected from a larger number in the original book, and folding in climate change messaging is like a dance. You need to deeply understand the dynamic of the game and what happens (or could happen if adapted). With that in mind you need to move your focus over to the climate change world and consider related dynamics, whether in the natural or human (political/economic/social) systems. Then it is an iterative thought exercise to bring those two elements together so that they work elegantly together in the end and are not too contrived.

Sometimes it is very obvious how the game and the key climate change learning points link and relate. And sometimes it is like doing sudoku in your head. It took us from 6-8 hours per game (so far) to make the connection strong enough to use.

There are different ways to make this link (between the game, climate change and systems thinking). You can change the frame of the game to put people in a climate-related context while they play. You can use the debriefing questions to guide people in making the link with the climate debate or dynamic. You can put in data, an observation, quotes from climate specialists, or elements from the news and current events to anchor the game to climate change. Or in some cases you can play the game and ask people what the link is (of course you need to have an answer too in case you draw blank stares).

We tried all of these approaches in the test workshop for our 20 games. They all worked in different ways. Of course, we were fortunate to have a room full of climate and games specialists, which our partners from GTZ (GTZ Climate Task Force) had invited, to play through the games, analyse them and give us great feedback to further strengthen the climate learning.

Our agenda was simply a list of games, and our table of contents will be that too. So we wanted to create a of narrative that held them together, a thread that helped facilitators and educators understand how they might use them. We created two organizing principles for the games day, which we will also use for the book.

First, we used a systems “map” as the organizing principle. This was a stock and flow diagram with stocks such as CO2 in the atmosphere/ocean, heat in the atmosphere, and ice cover, and flows like CO2 emissions, heat in, heat out, ice melting, etc. We had that up in our workshop room and positioned the message from each game around these elements (sometimes before and sometimes after the game). It was not too much of a stretch to map out the lessons from the games – some of which were about natural aspects, and some were more human system dynamics with communication messages, collaboration and competition, etc. We found it useful, and people appreciated this signposting to pull the games together.

The second way of clustering the games was by use. Some of the games are mass games which can be used for large audiences, who might be sitting in an auditorium. They can be used during presentations and speeches to make points, and people can play them sitting in their chairs. Some of the games are demonstration games, which a small number of volunteers can play for a larger group of say 35-50, and the lessons will become obvious to both those playing and watching. The third type of game is a participation game which everyone needs to play to draw the learning, so this would be for a typical workshop size group of 10-25 people.

We also used materials as a criteria for selecting the games initially, not wishing to have any of them be too materials/equipment intensive. In the end, our games kit included: Ropes, balls, coins, paper cups, markers, scrap paper, pens, hula hoop (collapsible), ball of yarn, a newspaper, and a rubber chicken. (I always worry about a customs agent opening my bag in a crowded place.)

We spent 8 hours that day playing our games, each of which run from 2 to 25 minutes in length. We used a 10-minute plenary discussion after each game to identify with the participants ways to strengthen either the game mechanics or the climate change frame and lesson. We also used a Games Review Sheet, so that people could note any thoughts they had during the day individually. I came away with over 50 pages of notes and ideas!

We are now integrating the ideas, revising our games and their write-ups, each of which is from 3-5 pages and written for the facilitator. There is still plenty of writing to do to produce the book and we hope to finish in July. It never made sense to sit at our desks and write games. This test workshop was an important and useful step in the process. There is a saying in gaming that you have to test play a game 10 times before it is really good. We have all played these games dozens and dozens of times in their original format. But they’re different now in some subtle and important ways, so this was an important step in “the making of” The Climate Change Playbook.

.jpg) Some people ask for examples of how systems thinking can be applied. Here’s a story that I came across recently…

Some people ask for examples of how systems thinking can be applied. Here’s a story that I came across recently…

Imagine you are a headquarters-based training unit in a big organization and, among other things, you put out a two-page newsletter each month that features short paragraphs describing all the different training activities that the many field units are conducting. Collecting the articles is hard work, you need to bug people all the time to send something in. Finally you get your quota of news and you publish it. At the end of the newsletter, you write “For more information, contact info@ourunit.org “.

Early on, after you would publish the newsletter you would get a string of requests for more information that needed follow up, which took quite a lot of time – going back to all the various authors and asking them for information, or passing along the request and checking that they answered it. It would take a while for the author to respond to you, the central HQ unit, then you would send back the information to the person who requested it. It took so long to get the information, that the perception of responsiveness of the HQ unit started to be affected, and eventually no one asked for more information. It started to get even harder to get trainers to answer your news request, you might eventually need to cast your training news net wider, which would need more research and take more time.

You find you are spending a lot of time administering this information exchange. And actually from the lack of timely response from the trainers, and feedback from your readers, you are not sure what kind of impact this is having. As a result this newsletter might not be at the top of your To Do list. Is it time for the newsletter again?

So what are our opportunities here?

You are putting a lot of energy into making this newsletter work. Is there something that you could do differently that would drive this process for you? How could you get the system to do your work for you, rather than you having to do everything yourself? Maybe there is something in the structure of the system that is currently operating that is making it less efficient than it could be. You are clearly in the middle of it. Can you step aside, and shorten some of these information pathways?

What if, instead of putting “For more information contact: info@ourunit.org” at the very end of the newsletter, you put, “For more information write directly to Trainer SamSmith@hisunit.org” at the end of every article? What does that simple change do? Well, for one thing it lets people send their requests directly to Sam or whoever, and you don’t have to get in the middle of all this correspondence. It puts a name and potentially a face to the training (can you put the photo of the trainer by his/her article?), and might encourage more contact between the readers and the trainers. Someone will see Sam now in the corridor on his visit to HQ and be able to talk to him about his training, rather than not knowing who conducted it.

Putting Sam’s name on the article serves to raise his visibility as the owner of the activity. He now starts to get some notoriety for his articles, and when people contact him for more information he gets direct feedback on his work. His article might bring him some new contacts, new internal clients, or potential partners. People will start to know more about what Sam is doing and when they are conducting training on a similar topic, they might bring him in. Sam starts to see the value of this reporting activity, and this incentivizes him to use that opportunity and to get his articles in on time; it becomes a great marketing route for him and his team. He might even improve the quality of his article because his name is on it now, instead of some anonymous info-email address in HQ.

Now, when the articles come in to you on their own, the quality is better, and you have more enthusiasm from the trainers, your task putting together the newsletter gets easier and more enjoyable. Your admin time goes down, and maybe you can spend more time instead finding new authors, or starting a friendly competition for the best writer of the year, the most prolific writer, the one that receives the most comments, etc., or working with existing trainers on their writing skills, or maybe you can start to find photos (where you never had time for that before). Now instead of having to free up days of work to get the newsletter out, it might be more like hours, and the newsletter can move up your to-do list.

This process starts with a good question – asking yourself if there is something that you can do to trigger reactions in the wider system that can sustain the positive effects of your actions. That is using systems thinking. You want your effort to achieve progress without constant energy input from you; so you ask yourself, what can I change, even with a small strategic effort, that can create a situation where other people, those centrally involved, are happily doing this work (instead of me)?

In this particular case, incentivising the trainers by giving them more visibility and shortening the feedback time from their readers would be a good and simple move. You might consider as a next step putting your news on a blog, and cultivating a set of trainers who would get a kick out of blogging about their activities, and could even post their own articles instead of you (you could give them a set of guidelines and some support). Then if you still need to publish a newsletter, it would be as simple as going on the blog and pulling off the top articles (SiteMeter could even take the guess work out of that) and republishing them in hard copy for the field based staff. The biographical information on the trainers/bloggers, the instant gratification of publication, along with the instant feedback they would get in the comments section would continue to incentivize them to give you timely, high quality content. Now, your newsletter project is just a quick activity, instead of falling into the pulling-of-teeth category of work. And as a bonus you get a lot of happy higher profile trainers, engaged, proud of their work and potentially more productive as a result.

All that from changing the contact information? Systems thinking!

(NOTE: Of course systems thinking would also have you asking, what kind of resistance might I encounter when I make this change to my system? How can I curtail that before it gets to me? And the systems thinking goes on…)

I am way behind in my blogging, mostly because I have been completely obsessed with another blog – one I set up in July for my Father that is not as different as I had imagined from this blog on Learning. The topics are very different, his blog (Outdoors with Martin) is about squirrel hunting, building farm ponds and the best places to catch large mouth bass. But his orientation is purely “how to” which definitely appeals to my learning side.