One of the hardest things about using LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY® method (LSP) is just getting people to try it!

One of the hardest things about using LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY® method (LSP) is just getting people to try it!

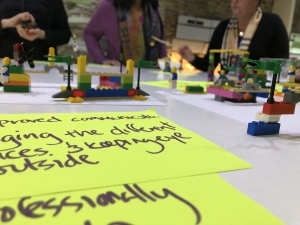

Imagine walking into the workshop room and sitting down at your spot to see, with your water glass, pen and paper, a small mixed bag of 48 LEGO® bricks – a LEGO® Exploration Kit. What’s running through your mind?

You might fall into two categories of people, the first one who says “Cool! Let’s play! No PPT – finally, not your ordinary workshop!” or the other one who says, “What? This is serious business, and time is scarce. Skip this silly stuff and let’s get to work!”

But before you even get into the room, there is a whole discussion that needs to happen with the workshop host in advance, where the Facilitator might get one or the other of those reactions after proposing LSP. During this conversation the Facilitator will need to explain the benefits, and give a little of its background…

Whose idea was it?

In the late 90’s, confronted by the tidal wave of video games that were taking kids away from their bricks, it was LEGO® itself who founded the LSP process, with a couple of IMD business school professors, to help the company think creatively and re-imagine itself.

The method worked, beautifully. Today LSP has a growing community of certified LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY® method facilitators connected together in an Association of Master Trainers, of which I am proud to be one!

Who’s using LSP and why?

I would say that LSP is becoming fairly well known in the private sector, many of the facilitators I met at the recent LSP community meeting in Billund, Denmark – the home of LEGO – worked with businesses, but not all. It seems to be just beginning in the NGO and inter-governmental/United Nations world, where I find myself working most. I’ve run LSP processes now with a number of first-time user groups, here are three illustrative examples of the organizations and what they wanted to achieve:

- a large international conservation NGO’s resctructured leadership team was undertaking a visioning process, and wanted to understand the features of a successful team in the future structure;

- a global reproductive health supplies team wanted to identify organizational priorities and explore efficiency and effectiveness in delivery;

- a small sustainability Think Tank wanted to focus on building excellent internal and external communications, and identify capacity and skills needed to do this.

The applications of LSP are vast, from strategic planning, design thinking, product development and marketing, rapid prototyping ideas, work process re-engineering, prioritization, as well as softer goals such as identifying what makes a good team member, how to build trust, and how to resolve conflict.

How can you do THAT with LEGO®? Thinking with your hands

The basic LSP process involves four steps:

- Asking a question

- Building a model (with the bricks)

- Sharing and explaining your model

- Reflecting on meaning

This four-step process happens over and over in an LSP session, with various other rules and parameters sometimes added. The process provides the builder the opportunity to think about her/his answer to the question (and the questions can be incredibly complex or blissfully simple), and then to use their hands and the bricks to build a metaphor that illustrates their answer (not a literal answer, but a metaphorical answer). Often people build as they think, they re-build, they explore their answer as they think and layer meaning onto the bricks. This process, of turning thoughts that might have started out rather vague, into 3D objects, helps people become more concrete about their thinking.

This nuanced work would be hard with a pile of only the traditional rectangular and square bricks, so the LSP brick sets are full of metaphorical pieces in addition to these – flags, mini figures, animals, flowers, propellers, etc. – to release the creativity of the builder. You still have to get familiar again with how things snap together, and even working with metaphor, so a skills building component is always included in an LSP session.

A number of Core LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY® application techniques have been developed by the Association of Master Trainers. These are illustrative of some of the most commonly used and thus most documented applications, and build on one another:

- Building individual models and stories

- Building shared models and stories

- Creating a landscape

- Making connections

- Building a system

- Playing emergence and decisions

- Extracting simple guiding principles

These generic techniques can be applied widely to different team and organizational goals, and are customised through the framing and question that is asked (What are our blind spots? What will our organization look like in 5 years? What does a perfect co-worker look like?), and normally involves some sequencing, where models are built and deconstructed (also a good lesson in letting multiple ideas come and go) with a strategic set of relevant, thoughtfully framed questions.

What changes in the individual?

There is some nice research underway exploring the value of LSP in working settings, and the changes that can occur in the individuals and teams participating. Some that we heard about and discussed at the LSP Community Meeting included:

- helping people enter a more reflective and thoughtful state, rather than getting off-the-cuff answers that might be the first ideas that pop into your head, thus the easiest ones, and perhaps not the most creative ones;

- helping people appreciate other perspectives – building the different models individually and sharing them helps people see what other people see (literally);

- helping people explore sensitive issues – building a model and using the model as a metaphor, even holding it or pointing to it as one speaks, helps to externalise the issue from the builder, making it easier to explain and less risky. The thinking has already been done, so people are not trying to think and talk at the same time;

- helping people develop more creative confidence – to feel more confident being creative in the workplace, especially in a rapidly changing environment where innovation is needed, both at the organizational level, as well as in terms of products and services.

It definitely takes courage to try something new, but I can report that all the groups that I’ve worked with using LSP have loved it, for the uniqueness of the process, the fun and engagement it provides, and ultimately for the deeper insights and creative results it produces.

What kind of creative process produces ideas like a

What kind of creative process produces ideas like a

What are your talents and your key strengths? And what are you doing to maximize these day-to-day?

What are your talents and your key strengths? And what are you doing to maximize these day-to-day?