There are so many kinds of workshops/meetings/events, with as many different kinds of objectives and outcomes desired. Each needs a specific structure and build to get successfully from start to finish. For veteran facilitators this might be a statement of the blindingly obvious. However, we do have our favorite sequences. We have tried and tested frames for group work, our signature activities and games, our question stems that we draw on and adapt to many different contexts. We might also do more of one kind of workshop than others – more retreats, or relationship building, or strategic planning, or stakeholder dialogues. These big categories indeed might have archetypal sequences that we can use as building blocks and rely on for winning results.

When the Stakes Are Even Higher

When we get into a new category of work, that is a great opportunity to think again about our favorite workshop outlines. For example, how different might an agenda look if you are consensually negotiating a text that will be binding on those in the room (and many others who may not be)? This is an interesting context as stakes will no doubt be much higher. In this context, participants may be formally representing constituencies (where their re-election depends on successfully serving their interests), others may be spokespeople for higher-level absentee decision makers (who may sign their paychecks). There might also be observers, funders, hosts, and other non-voting participants, who might still have significant impact on the final decision. There may also be significant power asymmetries, along with the familiar cultural and sectoral diversity and personalities that we see in all of our workshops. Ultimately jobs and much more may be at stake. All together this might make agreeing on a black and white text in a defined period of time an exciting couple of days for a facilitator.

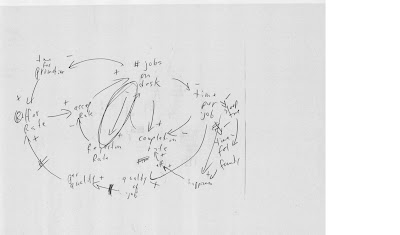

Some of the differences between such an agenda and one devoted to, for instance, strategic planning by project teams, might be how and when you work with the product (text) itself. Some of the things I have noticed revolve around timing and placement of the decision moments in the overall workshop agenda. These might sound simple, and can make a difference for a successful outcome:

- Watch attendance and travel: If this is a high stakes decision-making meeting encourage people to be there for the duration of the meeting, and if necessary make an agreement that if people choose not to stay it indicates their agreement of the final decisions of the group.

- Have clarity on decision moments: Make certain participants are clear WHEN the readings will be and decisions taken, so that they can arrange phone checks or access to other decision-makers at critical times. It helps them avoid scheduling other work or calls at those times and also helps them arrange their schedules to be present (mentally and physically) when they need to be.

- Keep extreme realism in timing: Because timing will be important throughout the event, keeping to time is even more important – make sure this particular agenda is super realistic (as opposed to optimistic), and build in some extra discussion time where possible (can a less important agenda item for the group be pushed into their next meeting?)

- Make it visual: When it comes to the text itself, make sure that the text is put up on PPT point or visually in the room and not just read out loud to the group. The meaning is much clearer and easier to discuss as a group when people are able to read and mull it over together.

- Externalise the decision: Making it visual (rather than oral – as in reading) also externalises the words (e.g. de-personalises the text) so that the group can own it and it is not affiliated with any particular position or the opinion of the reader(s).

- Provide something to take away: Have a print out of the final text too, that people can use to check with counterparts who are not present, or can use to read later on their own or in caucuses. Don’t make people write it down for themselves.

- Build in check-in time: Give people time after the first reading to check with their constituencies if necessary or with their bosses.

- Sleep on it: Try to get the text work done before the last day, so that people can sleep on it and discuss it informally.

- Take a second look: Have a second reading of the decision taken on the final day. Make sure this is not in the last few hours of the workshop in case there are still open issues which can be dealt with in time.

- Don’t push it: Introduce no new issues on the last day of the work together.

There are many other familiar activities that can and will feature along the course of the negotiation. There will be the relationship building, the mapping of opinion, the exchange of perspectives and reality checks. With this kind of high stake workshop, the steps of the negotiation and decision-making process need to be perfectly placed so that this central aspect of the group’s effort doesn’t create a hurdle but a gateway to … (ok, giving up on the horse-racing metaphor here, it’s sounding more like the stable floor than the track – you know what I mean!!)

This morning I went to an interesting Writer’s workshop on publishing – it ran the gamut from traditional book publication to online self-publishing. It reminded me of some of the things that I had learned doing this myself, which I had never recorded. So before I forget, I thought I would blog this experience for my own future reference, and anyone else interested…

This morning I went to an interesting Writer’s workshop on publishing – it ran the gamut from traditional book publication to online self-publishing. It reminded me of some of the things that I had learned doing this myself, which I had never recorded. So before I forget, I thought I would blog this experience for my own future reference, and anyone else interested…

.jpg)

8. Test it: Who is the authority who will announce the winner? If appropriate, do you have on hand the “suggested answers” and someone who can explain them?

8. Test it: Who is the authority who will announce the winner? If appropriate, do you have on hand the “suggested answers” and someone who can explain them?